|

Back

Where Admiration Vies with Adoration New York

SubCulture, 45 Bleecker Street

01/09/2014 -

“Reflections of Walter Piston, his colleague Aaron Copland and his student Leonard Bernstein”

Walter Piston: Improvisation – Passacaglia – Sonata for Piano (New York Premiere) – Concerto for Two Pianos Soli (arranged by the composer from his Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra) (New York Premiere)

Aaron Copland: El Salón México (transcribed for two pianos by Leonard Bernstein)

Igor Lovchinsky, Matthew Graybil (Pianists)

Melvin Stecher, Norman Horowitz (Speakers)

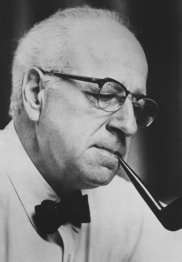

W. Piston (© Associated Music Publishers Association)

None of who have tried sloughing through Walter Piston’s iconic books on Orchestration and Counterpoint would have come across the composer’s method of composing. But two pianists who worked with the composer enlightened the audience at SubCulture last night by revealing Piston’s explanation of the compositional process to a child:

“First I sit quietly at my desk for an hour. Then I take a pencil from my pocket. Then I make a dot on a piece of paper. Then I wait for an hour. And then I erase the dot.”

One doubts that duo-pianists Melvin Stecher and Norman Horowitz would have taken it seriously. For Walter Piston–as teacher, writer and of course composer–was a most serious artist, as was proven last night by two other duo-pianists.

Piston is rarely played in New York these days. In fact a search through ConcertoNet shows not a single review from 1989 to the present. He had taught the entire hagiography of American composers from the 1930’s to his retirement. But nobody would dare pigeonhole Piston with one adjective. He is not “jazzy” Bernstein or “folky” Copland or “eccentric” Cage or “antediluvian” Carter.

At the same time, his work, while depending heavily on classical models, balances precariously on the academic and is never pedantic. He wrote the book, yes, he was a master of his craft, but those “dots” were always inspired.

Still, an evening of Piston “music for solo piano” is oxymoronic. He wrote an early Piano Sonata, one Improvisation, one Passacaglia and...well, that was it. Last night had to be filled in with a transcription of a concerto and a piece by Aaron Copland.

M. Graybil/I. Lovchinsky (© Courtesy of the Artists)

Two young prize-winning pianists, Igor Lovchinsky and Matthew Graybil, were totally committed to Piston. To accomplish this, they had to have more than faultless technique. They had to possess the refinement of Piston himself. They had to show that classical and Baroque models–sonata form, passacaglia and fugue–could be played with the apparent (if deceiving) ease in which Piston composed.

Mr. Graybil took two short mature works by Piston and gave them a formal finesse. The 5/8 theme of the Passacaglia was built into a structure that was powerful, without being overpowering. The Improvisation was more than a bagatelle, but a finely worked-out model played with beautifully worked out feeling.

The Sonata, played by Mr. Lovchinsky, was not only new to me, but was New York premiere. It was written in 1926 while Piston was studying in Paris, and once again showed that Parisian refinement, albeit with a finale fugue which was indeed overpowering.

The Two-Piano Concerto, commissioned many years ago by Messrs Melvin Stecher and Norman Horowitz, followed the anecdotal, enlightening and highly personal talk by these pianists about their relationship with the composer.

The Concerto itself, without orchestra, was Piston at his most varied and mature. He had left Paris and the music was percussive and lyrical, sometimes a bit frenzied, more often keeping the excitement in check. And played with fludity and balance by the two artists.

If revelation was to be heard, it wasn’t in Walter Piston. In a way, his music was so brilliant, perfectly woven and caring, that it induced admiration without adoration. His music was vitally feeling (as in the second movement of the Concerto), but with an almost physical refinement.

But the revelation was El Salón México, the two-piano version of Piston’s colleague Aaron Copland by his student Leonard Bernstein. Of the three versions of this, Copland’s first “folkish” work, the two-piano version I feel is the finest. The original orchestration is a Technicolor glittering painting of a Mexican dance hall. Bernstein’s single-piano transcription is perhaps too one-dimensional.

But the two-piano version shows what is so well-hidden in Copland’s more popular pieces. His extraordinary counterpoint, his bi-rhythmical textures. And when played with such clarity by Messrs Igor Lovchinsky and Matthew Graybil, one hears Copland as the most marvelous magician.

In fact, it answers a question posed at the beginning, why Piston is respected more than performed. Walter Piston’s scholarship, his Gallic playfulness, his inspirations are elegantly all on the surface. We have no mysteries to plumb, no gems to remember. Aaron Copland’s popular music uses these same tools with the same impeccable skill. But they are used to project a message in which our appreciation is tertiary to our emotional involvement and our unalloyed delight.

Harry Rolnick

|