|

Back

Zest and Zeitgeist New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

12/02/2012 -

Sofia Gubaidulina: In tempus praesens

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5, "Emperor", op. 73

Igor Stravinsky: Firebird Suite (1945 version)

David Chan (Violin), Yefim Bronfman (Piano)

The MET Orchestra, Fabio Luisi (Principal Conductor)

F. Luisi, Y. Bronfman (© Carnegie Hall)

Composed almost exactly 200 years from each other and performed after each other, the two concerti of the MET Orchestra had one commonality yesterday afternoon. Both Beethoven’s “Emperor” and Sofia Gubaidulina’s In tempus praesens represent the essence, even the zeitgeist of the early 19th and 21 centuries.

The Beethoven Fifth Concerto was linear, forceful, logical, a triumph not only for composer and (hopefully) pianist and orchestra, but exulting for an audience in the Age of Enlightenment, aware that European history was bound to change for the better. It is a work of exterior secular victory. For Beethoven, even Tragedy was the opportunity for Triumph.

Ms. Gubaidulina is not only the scion of an international heritage never imagined in Beethoven’s Vienna–she comes from a Tatar family, her grandfather was a Muslim Mullah, and her mother was of Russian, Polish and Jewish heritage–but her music has an eclecticism embracing more than Beethoven could imagine.

What, indeed, would cranky old Ludwig make of a piece which the composer herself calls “architonic modes of form”, the “changing psychological conditions of man, how it lapses in nature”? How would Beethoven, always thinking and lucid conceive of a woman (“A woman??” he might snort) who feels her music is “situated between sleep and reality, between wisdom and folly...”?

Beethoven would not have scorned such thoughts. He might have embraced them (Prometheus versus Morpheus), or argued against them the way Mahler argued against Sibelius in the meaning of music.

But listening to this work, meaning “For the Present Time”, he would have understood the triangular structure, the manifold references to Bach (the blatant chorales, the intrinsic counterpoint), and even–just perhaps–the intimations of mysticism. Beethoven, for all his secular leanings in the age of reason, knew that his inspiration came from Somewhere, And he was absolutely fascinated, as all German philosophers and artists of that time were, with India, metaphysics, the Transcendental, with Fate.

For the audience yesterday afternoon, hearing both works, so serious and yet so highly emotional in their own ways, was not the easiest things to do. How does one listen to Ms. Gubaidulina’s violin concerto, luscious, glowing, yet oracular, its meanings hidden, preceding Mr. Beethoven’s piano concerto which lays its heart on its keyboard, which proceeds forward with untroubled valor?

Not easy. But fortunately, the artists who performed were so interesting nobody could help but be entranced. (I’m wrong there. The well-dressed man in front of me refused to applaud the violin concerto and left before the Stravinsky. That was his problem...)

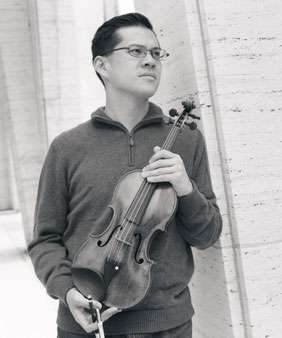

D. Chan (© Karen Hill/Juilliard)

I had heard Anne-Sophie Mutter–for whom Ms. Gubaidulina’s work was dedicated–play with the most delicate colors, her high notes (the solo plays almost entirely in the stratospheric region) ringing out with the most stunning colors on her Strad. But David Chan, while technically more than able (being Concertmaster of the MET Orchestra is not exactly for amateurs), took a more literal stance, and allowed the unique orchestra to have its say. Yet during all 33 minutes, I doubt if Mr. Chan could rest for more than a measure, with virtually every series of phrases turned into a quasi-cadenza.

When Ms. Gubaidulina specifies “strings”, she means no violins and double-basses with five strings. Thus, in contrast to the soloist, we had a deeper, more subterranean sound. But the piece is more than unusual strings. Against Mr. Chan’s playing, we had deftly orchestrated repeated fortissimo chords, the most delicate music including harpsichord and harps, and a full panoply of sounds which were both volcanic and microscopically singular.

Where Ms. Mutter had soared above the New York Philharmonic when she performed last year, Mr. Chan allowed a wider scope for the orchestra to drift in and out, make its statements, drift off again, announce a new series of sounds and then–as in dreams or drug-induced hallucinations–fall away.

At the end, there was no possible way I could stand in the intermission and shmooze. I needed the rather balmy New York air before the second half.

One had no doubt that Yefim Bronfman would not “tackle” the Beethoven Fifth Concerto. Whatever he plays is his, the only challenge that, with his strength, overwhelm the orchestra or conductor. His excellent taste precludes that possibility.

But even more than those demonic octaves and electrifying velocity was his unerring lyricism. How he could segue from bravura intensity into translucent melody is Mr. Bronfman’s secret. We poor mortals might never solve the mystery, but his playing is so gorgeous that we don’t want to find out.

I’ve not mentioned the Metropolitan Opera Principal Conductor (under Music Director James Levine) Fabio Luisi, but the MET Orchestra got a full workout under his baton, ending with the “chamber” suite of Stravinsky’s Firebird.

Chamber version? After the Beethoven orchestra, Carnegie Hall’s stage was bursting from one end to the other with instruments, all of which were kept in place by Mr. Luisi. It was a brisk, no-nonsense Firebird, the demonic dance was fiercely devilish, the end was suitably uplifting. A few idiosyncrasies (Mr. Luisi played those final downward scales staccato rather than fluid), but it was a terrific ending to a singularly absorbing program.

Harry Rolnick

|