|

Back

Breathless, Not Breathtaking New York

The Allen Room, LIncoln Center

10/25/2012 -

White Light Festival: Higher Vibrations

Various original works

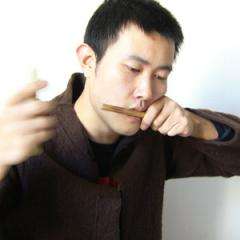

Wang Li (Mouth Harp and Calabash Flute)

Wang Li (© Hai Zhang/White Light Festival)

Almost any superlative can be used for Wang Li’s concert last night. Call if magical, mystical, astounding, bewildering, brilliant, other-worldly.

The only adjective not applicable is breathtaking.

Indeed, for several of the dozen-odd works Wang Li played over an hour, he took not a single breath for four or five minutes at a time. In fact, for one piece (they were untitled), playing the calabash flute, he was working with three notes at a time, with a constant bagpipe-like drone, peppering the music with beats and grace notes, harmonies and rhythmic thumps. And I found it impossible to detect a nanosecond where he could have taken a breath at all.

Opera singers can master the art of circular breathing, and I suppose Wang Li has acquired the same skills. Yet such tricks of the trade were secondary to the magical art of his sounds themselves.

Wang Li uses only two instruments, both of them considered primitive. I have heard the kouxiang, the mouth-harp, in Cambodia and Thailand, and imagine it is used in the mountains of Yunnan among the tribal people, Its only “classical” use was in Charles Ives’Holidays, but the twang there was fairly crude.

Wang Li’s mouth-harp has three tongues, but the sounds were made by the workings of the mouth, lips, tongue and probably deeper down. Wang Li began with a kind of tinselly ringing sound, but over the evening made it into gongs, hollow caverns, treble booms, and actual trills with different timbres.

The other instrument was the calabash flute or hulusi. This resembles in shape the Indian “snake-charming” flute, but the sound is not only deeper, it is a multi-toned instrument.

Its equivalent is the Laotian khaen, which looks like panpipes, but has the same idea as the hulusi. With the khaen, one note is played as a drone with no help from the player. The other fingers play the notes in a kind of bluegrass syncopated rhythm. (I know this only because many Westerners, who find Thai music alien, love the sound of the khaen and learn to play it.

But there is no way we could begin to hear what Wang Li was doing. That bagpipe drone in fact, was constant, but the sounds which he created over two octaves, from a bass clarinet timbre to soprano sax, were diverse, colorful, filled with vigor and lightness and….well, superb artistry.

Yes, Wang Li employed some electronics to amplify this music. At first he seemed to have a whole orchestra of electronics to make things so interesting. But Wang Li, though far from being a minimalist, limits the tools. The woofers and sub-woofers are used to amplify the sounds to the audience. The reverbs were sharply controlled through his hands (he controls his own sounds like a theremin), and his whole array of voices (even at rare times his own voice along with his instruments)

How did this phenomena come into existence? Wang Li has unique musical curriculum vitae. Not from China’s central cities, he was born in the harsh Northeast on the Yellow Sea. He started playing the Jaw’s Harp, but switched to the electric bass guitar and was soon playing in Western-style rock bands.

Now the magical difference begins. Instead of continuing, he went to France and entered the seminary of St Sulpice at Issy-Les-Moulineaux, living as an acolyte monk (a contemplative) for four years. He emerged from here to go to the Paris Conservatory, studying jazz and improvisation.

Returning to China, he reverted neither to jazz nor rock, but he began a deep and intensive study, not only of Northeast China folk music, but probably journeying to the West. I would imagine Yunnan was where he picked up some of the instrumental techniques he played here. And after this, he somehow merged background learning and art into this somehow mystical, atavistic, contemporary and frankly chimerical categories we have today.

And finally to the performance itself. One would have thought that, against the background views in the background, Wang Li might have been dwarfed. Quite the opposite. Once those tiny sounds came out, erupting into louder, pure musics–no simple replicas of birds or rivers or storms from this very pure musician–one was instinctively transported to another land.

While Wang Li has performs at innumerable folk festivals, little is folkish about this music. One is transformed by the sounds themselves, not the origins of the instruments. One is mesmerized, not so much by his technique, as the results of the technique.

From his few charming words (one imagines his French is better than his English), one hears the word “dream” used several times. The dream of being in New York, and dreams which are evoked in this music. And the sounds he makes are those which seem to appear in a dream. Unearthly, unmaterial, entirely their own world.

These weeks New York is having a series of concerts devoted to John Cage, another composer who reveled in sounds and silences. True enough, some of Wang Li’s music resembled the Cage pieces for miniature piano. But Wang Li is an artist who doesn’t worship sounds for their own sake. His mouth-harp, his flute, were used last night to create a mood which created and soared the music another world.

At one point, he said to the audience, “I don’t know if you are in my dream or I am in your dream.” This is the sentiment of a Taoist, a mystic an artist. He and we whirled through the same dream, and waking up after an hour, we knew we had shared the experience of the delightful universe next door.

Harry Rolnick

|