|

Back

Earth: Sounds and Silences New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/31/2023 - & March 30, April 1, 2, 2023 (Philadelphia)

John Luther Adams: Vespers of the Blessed Earth (New York premiere) [*]

Igor Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring

Meigui Zhang (Soprano), Charlotte Blake Alston (Speaker)

The Crossing, Donald Nally (Music Director, Conductor), The Philadelphia Orchestra, Donald Nally [*], Marin Alsop (Conductors)

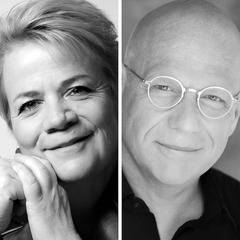

M. Alsop/D. Nally (© Nancy Horowitz/Stuart Wolferman)

“By shallow rivers, to whose falls/Melodious birds sing madrigals.”

Christopher Marlowe (1564‑1593), The Passionate Shepherd to his Love

“When I heard the learn’d astronomer... I wander’d off by myself, in the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,/Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.”

Walt Whitman

Mahler was missing, but he would have been pleased that the two works played by the Philadelphia Orchestra last night could have been titled Songs of the Earth. John Luther Adams’ 50‑minute Vespers celebrated–or sometimes mourned–the earth as we knew it and know it. Unlike his ten thousand birds, this gloried in the past, with ominous shadows of the future. Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring saw the savagery of the peoples of the earth. How they worshiped nature by rape and abduction, with the rumbles of the earth part of the terrors of the human.

And while the two works hardly bonded the earth gave us telling relationships for both.

Stravinsky’s Act One Introduction could have been written by Mr. Adams: dissonant chirping, isolated and flocks of birds. In John Luther Adams’ Night Shining Clouds, we had, below the high strings, an ominous sound of tectonic plates rubbing against each other. The same kind of pre-human rumbling terror of the Stravinsky.

Yet these were two separate works–and they utilized two different conductor to make their mark. The Philadelphia Orchestra Artistic Director Yannick Nézet‑Séguin was ill, so the Philadelphians enlisted two extraordinary substitutes.

Donald Nally is orchestrally famed. But his star is with The Crossing, a chamber choir commissioning and premiering works by eminent composers, as they did last night. Marin Alsop garnered greater applause before Sacre entrance–because much of the audience knew her from frequent references in Tár.

(That, though, was hardly appreciated. After seeing the film, Ms. Alsop had declared, “I was offended as a woman, I was offended as a conductor, I was offended as a lesbian.”)

This aside, she created a dynamic Rite. And while she might have resented it, her physical prowess equaled the music velocity.

More on that later. For little could be more contrasting that John Luther Adams’ Vespers of the Blessed Earth. Like the title, Mr. Adams’ music in total is for a reverence to the planet and all its creatures. He once claimed that his music “began with birds”. But these are not Messiaen’s mystical birds. His musical references in ten thousand birds were literal bird songs. And in Vespers, he came close.

Despite the massive orchestral resources, Vespers was markedly quiet. “The Crossing” started a first movement with mainly high voices intoning (in Mr. Adams’ words) “two‑billion years of deep time through singing the names, colors and ages...” This was followed by the a cappella chorus imitating, giving canonical variations to that of a single New Guinea bird. Even without that, the mysterious almost Kabbalistic singing was like a prayer.

J. Luther Adams (© Chris Lee)

In “Night Shining Clouds”, Mr. Adams continued with an orchestral paean. Almost silent–except for a rumbling in the basses, a sound I felt was like a Tectonic explosion deep under the earth. The fourth section, was theoretically simple. A choral announcement of bird‑names–the Latin names of animals and plans either extinct or on the brink of extinction.

Finally soprano Meigui Zhang entered on stage for a vocalise, a shimmering, glowing, sometimes startling exequy to a Hawaiian extinct bird whose last song had been recorded in 1987. Ms. Zhang’s voice and music here was like a slow, wandering remote Magic Flute Queen of the Night. And while I am not prone to crying at mere program notes, the reference to the sounds of the last species on earth was heart‑breaking.

Like all of John Luther Adams, one was taken into his singular aural vision. One could not feel orthodox “excitement” or wish for it to be repeated. On the other hand, it did have its shortcomings.

Why did Mr. Adams (or Mr. Nally?) not spread out his singers throughout Carnegie Hall. The awe one felt for ten thousand birds was for the full instrumental ensemble to be spread out among the audience (which itself was prompted to wander around the musicians). Here, except for a spatial openness of the orchestra (double‑basses placed on opposite end of the stage), the ensemble had the usual orthodox demographics.

Next was the fault of the audience. All was chorus and orchestra until the last movement. When Ms. Zhang appeared from the wings, she was given the applause of an opera diva coming on for her opening aria in Turandot. Whatever spell was cast was immediately broken. Put the soloist in among the chorus. Have her come out like Venus from the Cypriot waves.

After the intermission, Marin Alsop appeared for another song of the earth. Silence became hammering, thundering percussive, fierce and flaming Stravinsky. And the Philadelphia Orchestra crushed out Mr. Adams’ silence and birdcalls. Ms. Alsop is a highly physical force, and she weaved, bobbed, jumped and cued in every timpani blow, every cornet scream.

Mr. Adams’ avian Elysium was morphed into Stravinsky’s barbarian earth‑tremors.

One more outré affinity between the two works, written 110 years apart. The fifth section from Vespers of the Blessed Earth sings the sound of the Hawaiian Kaua’i ʻOʻō bird, recorded in 1987, the last sound of a bird now extinct. Listening to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, one realizes that no orchestral work from 1913 to the present and the future, will ever be as great. Like the bird, it will never be repeated. Thus Sacre bespoke, in a quirky way, the death of music.

Yet Mr. Adams was inspired to know that the Kaua’i ʻOʻō could still cantillate, even for a non‑existent future. And we know that Rite of Spring would continue, even as the ultimate notes of orchestral music. Yes, the last of both species. Yet nature and music could still speak to the last syllable of recorded time.

Harry Rolnick

|