|

Back

Innocents and Anarchists New York

Lehman College Studio Theatre

09/10/2022 - & September 11, 2022

Marc Blitzstein/Leonard Lehrman: Sacco and Vanzetti (Orchestral staged premiere)

Christopher Remkus (Nicola Sacco), Michael Niemann (Bartolomeo Vanzetti), Perri Sussman (Sacco’s wife), David Aubrey (Prof. Richardson), Elliet Rae Baltitas (Dante), Sarah Blaze (Mrs. Evans), Desirée Baxter (Mary Splaine), Kevin Courtemanche (Police Officer, Judge, etc), Jonathan Z. Harris (Garage owner, Attorney etc), Karen Jolicoeur (Ruth), Andrew Klima (Anarchist editor, etc), Alyssa Mener (Assistant to Governor), Joshua Minkin (Anarchist, etc), Richard Risi (Clerk, MIT President), Benjamin Spierman (Governor Alvan D. Fuller of Massachusetts), Christopher Tefft (Police Officer, District Attorney), Helene Williams (Mary Donovan), Henry Yen (Jury Foreman), Nancy Zucker (Juror)

Metropolitan Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Lehrman (Conductor)

Benjamin Spierman (Stage Director), Joshua Rose (Stage and Lighting Design), Maxwell Bowman (Video Design)

M. Blitzstein/L. Lehrman

“...a true operatic theme. The rise to nobility...of two simple men in collision with specific chicaneries within the Establishment, driven chaotic and ultimately murderous...”

Marc Blitzstein, from interview in the Kansas Law Review

While outstanding composers can pride themselves on creative purity, Marc Blitzstein had a political purity which defied and define idealism. Hearing that Jerome Robbins had “named names” for the House Un‑American Activities Committee, Blitzstein tore up a work he had written for the choreographer. Working on an opera about a theme he passionately believed in–the trial and execution of cobbler Nicco Sacco and fish‑peddler Bartolomeo Vanzetti Anarchist Italian immigrants in the 1920’s–Blitzstein stopped working on it when discovering that it was being partly subsidized by the Ford Foundation.

What would happen with what Blitzstein had felt was his magnum opus? Franz Kafka had been rescued from anonymity by Max Brod. Blitzstein was hardly anonymous–The Cradle Will Rock is one of the great proletariat operas. Yet his opera Sacco and Vanzetti longed for a composer to finish it. Leonard Bernstein and others refused the job. Composer-conductor-pianist Leonard Lehrman took on the arduous task. Not simply of “finishing it” but writing two of the final three acts.

That finalization of Sacco and Vanzetti was conducted by Mr. Lehrman last night at Lehman College, orchestrated, staged by Benjamin Spierman and sung by a huge cast of very professional soloists of After Dinner Opera Company.

The result was inevitably a mixed success. The settings of the 15 scenes were brilliant. The prosceniums were cell‑bars, the backgrounds were grainy black-and-white photographs of each scene (grimy room, grimy garage, jail rooms). The actions of the performers were, in the first of acts, were fluid, exciting, highly dramatic. The singing was professional, though with few female roles, there was a sameness to the constant tenor-baritone combination.

Mr. Lehrman captured the Blitzstein idiom perfectly. I had only seen one Blitzstein opera, but I felt from the beginning that this was Blitzstein’s language. Not atonal (though close), not lyrical (though we had a dramatic monologue by Sacco, a deliciously funny whistleable-song by the joyfully clever Vanzetti, and his own monologue about making shoes. And a parody march about “loyalty”, sounding part Internationale, part Horst Wessel. Even a few bluesy measures.

Would Blitzstein had composed anything approaching an Italian opera aria? We’ll never know. Mr. Lehrman resisted the opportunity.

The result, alas, was anything but the intense drama conceived by Blitzstein. As usual, the composer wrote his own libretto. In this case, he apparently did the most intensive historical research, plumbing every book on the trial, the records, the letters of Vanzetti, every theory. That was all to the good. The challenge, though, to use what had to be used, and pruning anything extraneous to the creation of an opera or even a drama.

The first act (or First Part) had the makings of another Cradle Will Rock. A small chorus declaiming, Shakespeare style, that this was “the end”, giving away the story. This was the device of a fabulist. Following were more fables, each more concentrated than the other. Sacco’s house where friends warn him to hide is Anarchist pamphlets. One immediately is warned. A garage, where the racist couple detain both “Eyetalians” Sacco and Vanzetti who wait for a friend.

Then the arrival of two cops, looking for the “foreign-looking” killers. They interrogate the two in, easily, the most dramatic and musically telling scene of the whole opera. The questions, the answers, are like an antiphonal motet.

This leads to prison, the trial by obviously racist attorneys, that parade and finally, with their separations, the most brilliant solos of the evening. Both prisoners long to return to their Italian homes. Nothing sentimental in the Blitzstein-Lehrman music. After all, Sacco and Vanzetti were politically enlightened idealists, both of America and the workingman.

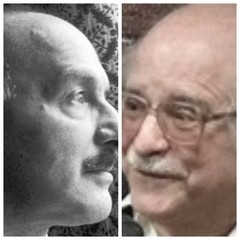

M. Niemann, C. Remkus (© Samuel A. Dog)

For Part Two, something happened. In effect, seven scenes which eschewed inspiration, where music became recitative, where words were neither dramatic nor operatic: they and the following scenes were didactic, sophistic, vaguely disputatious, and sadly endless.

“In the rooms, the characters come and go speaking of Barto and Nico Sacco.”

With such uniformly excellent voices, with such smooth stagecraft, I found these machinations not only lacking the semblance of drama or the emotion of opera. I feel that Marc Blitzstein himself, a master of movement, purpose, volition, would have simply torn the story in half. Sacco and Vanzetti were innocents (not necessarily innocent), they were hurled to death by a legal hurricane, and they should have controlled their final act.

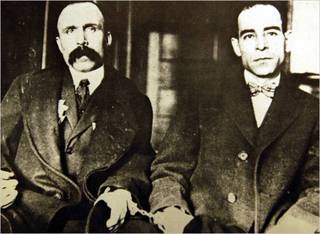

B. Vanzetti, N. Sacco

If the two men were victims of American injustice, avatars of anarchy, the last 15 minutes exemplified two other kinds of anarchy.

Technically, the ending was a mess. Mr. Lehrman, the consummate conductor for most the concert, suddenly lost his way. Rather, the orchestra lost its way, he stopped them several times, a violinist walked out, lines from the opera had to be repeated, the subtitles stopped, an important character was a minute late and the important lighting and video guys became utterly confused, as the conductor yelled up to the booth for better coordination.

Those things are excusable. They happen.

Artistically, those last few minutes should have been cut entirely. This had been a drama about two unhappy people caught in the claws of an unfeeling world, with a visual background showing the grimy scenes of injustice. Abruptly the background turned into a meaningless collage.

First a fleeting image of Ben Shahn’s famous painting, then a motley salmagundi featuring the Rosenbergs, some Nazis, Joseph McCarthy, and a dozen other characters, ending with–oh horrors!–a full screen picture of Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis (he had posthumously exonerated both Sacco and Vanzetti 50 years after their death).

It would be as if the last chords of Tristan und Isolde, instead of dying out, showed a potpourri with images of Naked Maja, Jane Russell, Adam-and-Eve, a Thai masseuse, Lili Marlene, and the gigantic image of Mae West.

Methinks Mr. Blitzstein would have looked with horror at the end of his opera. He was indeed a man of blazing political consciousness. But his genius was a dramatist of music, and this was a stupefyingly un‑musical, undramatic climax to a well‑meaning conception.

Harry Rolnick

|