|

Back

One Death, Many Transformations New York

Catacombs, Green-Wood Cemetery

10/06/2021 -

Osvaldo Golijov: Tenebrae

Franz Schubert: String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor (“Death and the Maiden”), D. 810

Ulysses String Quartet: Christina Bouey, Rhiannon Banerdt (Violins), Colin Brookes (Viola), Grace Ho (Cello)

R. Banerdt, C. Bouey, C. Brookes, G.Ho (© Courtesy of the Artists)

“No one feels another's grief, no one understands another's joy. People imagine they can reach one another. In reality they only pass each other by."

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

“Two messengers came to tell my friend the news of their son’s death. And as soon as they heard that, they went upstairs to wake up their younger daughter, who was 12 at the time. And the first thing she said to them was, 'But we shall live.'"

Osvaldo Golijov (1960– )

Did Franz Schubert’s 14th Quartet finally return to its pre-destined home last night? Death and the Maiden started life as a typically Gothic poem by one Matthias Claudius. The words were later enhanced with a song by Franz Schubert. Not satisfied with that, Schubert metamorphed the words into the strings of his D Minor Quartet, the quartet itself orchestrated by several composers, including Gustav Mahler.

Not satisfied with that, the Chilean dramatist Ariel Dorfman used the music for a harrowing drama called Death and the Maiden, which itself was transcribed for an equally harrowing movie directed by Roman Polanski, where the original music was both motivation and clue.

Der Tod und das Mädchen hasn’t yet become a Walt Disney musical (with both the maiden and death singing and dancing across the stage in front of a chorus of gay Satanic imps). But give it time.

Last night, though, the haunting Death and the Maiden found its most appropriate setting; Schubert’s Quartet was finally performed in the eerie candlelit Catacomb of Green-Wood Cemetery. Brrrrr...

This, added to Osvaldo Golijov’s Tenebrae (where the candles should have been extinguished as in the traditional Catholic services) made for an evening which–unlike Andrew Ousley’s other cemetery productions–should have produced shivers, crying and a feeling of death in the cathedral. That we all escaped psychological doom was due to the musical expertise of the Ulysses Quartet.

I’d heard them twice before: once in octets with the Emerson Quartet, and once with bits and pieces of modern music. Both times were satisfactory, yet both times I wished for some complete music. And this they accomplished last night.

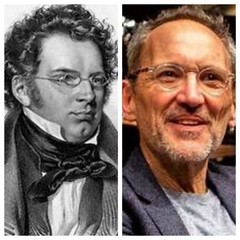

F. Schubert/O. Golijov (© Courtesy of the Artist)

With their youth and freshness, one would have imagined a melodramatic Schubert, swift, even tough, giving that second movement the piercing cries of an Edgar Allen Poe. But no, the Ulysses were more subtle than that (a Stephen King development?). Not that the variations were meditative. One heard a humanity, led by the sweet first violin playing of Christina Bouey, and the dark counterpoint of both viola and cello. In fact, rather than melodrama, the Ulysses Quartet, with their meticulous fingerwork, and their faultless ensemble playing made this less deathly melodrama and more deathly meditation.

Like a translation from the poem, this was not the Grim Reaper, it was Death soothing,Be of good cheer! I am not fierce,/Softly shall you sleep in my arms!.

The finale tarantella, far from being Satanic, is a challenge, in tempo and phrasing, for any quartet. The Ulysses Quartet, from the opening notes, showed that they are not individuals so much as a terrific ensemble.

The evening appropriated with another Manichean work of iniquity and resolution. In this case, Osvaldo Golijov started with the “wave of violence” he saw while on a visit to Israel, followed by a visit to a planetarium with his son, the latter awestruck by the heavens.

That was a magic libretto, and Golijov transformed it into a work of closely-merging strings, of dark slow-moving disssonannce. One might have thought the later pinpoints from the strings like light from the stars, but this would be too obvious for Golijov. The shadowy timbrewsremained throughout the whole 11-minute work. Yet a few measures of beautiful major chords offered the same humanity of Schubert. They both saw the skull beneath the skin, but we able to avert knowing eyes and their music to share a kind of radiance.

Harry Rolnick

|