|

Back

Notes Transcendent New York

Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center

03/03/2020 -

Johann Sebastian Bach: Chaconne from Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004 (Transposed by Johannes Brahms for the left hand) – Die Kunst der Fuge, BWV 1080 – Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, BWV 147 (Arranged by Dame Myra Hess)

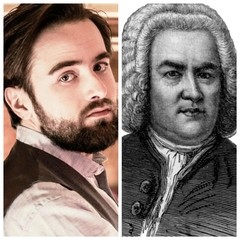

Daniil Trifonov (Pianist)

D. Trifonov/J. S. Bach (© Courtesy of the Artist)

“The fugue is not a form itself...but rather an invitation to invent a form. Success depends upon the degree to which a composer can relinquish formulae, and for that reason fugue can be the most routine or the most challenging of tonal enterprises. The final, unfinished fugue from ‘The Art of Fugue’ is the greatest piece of music ever composed.”

Glenn Gould

“For the glory of God, and for my neighbors to learn from”

Johann Sebastian Bach, from Little Organ Book

Nobody–neither pianists, audiences, or certainly not Johann Sebastian Bach–expected that Art of the Fugue would be played complete in a grand concert hall. Like his Cello Suites or Musical Offering or even the Brandenburgs, they were written as gifts, as textbooks, as showoff exercises. But they were never played in his lifetime.

Various pianists record the 21-odd Fugues, they were made for Glenn Gould’s straightforward studies in mathematical perfection. Hermann Scherchen orchestrated them. (In order, he said, that they ascend from the intellectual elite into the pubic consciousness.)

I had never encountered them in the New York concert hall. Not until last night, when Daniil Trifonov took these pieces, written on four separate staves and turned them into a Russian extravaganza of Romantic ecstasy. Whatever one thought about the rest of the program– Bach arrangements and encores by three Bach sons–The Art of the Fugue was a work of Titanic–and quantum–delight.

Yet how else could a master like Daniil Trifonov play them? He is hardly a shrinking violet, he plays his Rachmaninoff and Chopin as though reaching for the stars. So how on earth (or heaven) could he be expected to offer a dainty harpsichord simulation of music which had no instruments assigned? Give Fugues, a Steinway, the mighty acoustics of Alice Tully Hall, and the powerful powerful concepts of Daniil Trifonov, and one has the makings of an astonishing concert.

They were not to everyone’s taste, of course. The packed audience thinned out fractionally after the intermission. But mainly, Mr. Trifonov mesmerized listeners with his variance, his surprises, his constant changes.

Bach never allowed a single word of direction here, so obviously Mr. Trifonov was free to perform at whatever pace he needed, And as Glenn Gould inferred, the performer can use his own imagination to complement the composer.

Thus Mr. Trifonov could make a fugue into jigs, sarabandes, acrostics (the final one), into funereal obsequies. Lacking the concentration of the artist, my mind wandered at times into watching a juggler take six or seven balls of different weights and sizes floating, soaring, descending always being caught and thrown again.

Or–imagining that Bach in Vienna might have seen an Ottoman or Bukhara carpet– tens of thousands of threads in infinite directions, yet somehow encompassing the whole.

Mr. Trifonov, though, was intent on the music itself. The lines could go swooping down in mystifying complexity, and the artist never even tried to hide these quantum equations for “clarity”. At the same time, the original theme–whether inverted, diminished, inverted or played (as Schoenberg would say) “crab-wise”–was never far from the surface.

No matter how complex, no matter how far Bach’s mercilessly mathematical mind was breaking Newtonian Laws for the unexpected, Trifonov always kept his eyes and mind and fingers on that original treasure, the Bach theme.

My own notes give some description to individual sections, but I threw them away. Mr. Trifonov turned the separate exercises, experiments etc. into a complete universe of music. Purists might say he was too fast, too slow, too clever, too amiable, too funereal. Or that he shouldn’t have finished Bach’s last unfinished fugue, where he notated the name B-A-C-H half a dozen times.

Nonsense. Orpheus calmed the beasts. Trifonov never wrestled with this ungainly beast. He and Bach together projected vitality, energy and, above all, life.

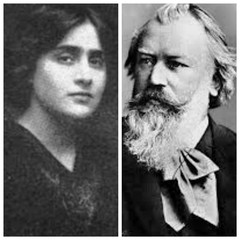

M. Hess/J. Brahms

Now we come to the other works, and how he constructed them for the program. The opening Brahms arrangement of the famous Chaconne was written for left hand only, possibly because he didn’t want to destroy the original delicacy of the original violin.

Fat chance. This was indeed Brahms–yet Mr. Trifonov played it with such mastery, such changes in color, in meter, in meaning, that it showed the Baroque mastery to be equivalent to the late Romantic mastery.

One could sympathize going directly into the Fugues eshewing applause before the major work. Yet we did need that space, that pause between the works. With a wave of his hand, he could have stopped the clapping, and given us a breath to digest what we had heard.

Still, that was his choice. Chaconne à son goût.

Dividing the fugues with an intermission was questionable (and even worse since a few dozen audience creatures left during that time.). Again, he left no space between the last fugue before the last piece.

Yet the following Myra Hess transcription of Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring was given a hard-driven performance. Perhaps he was saying that Bach’s cantata chorale was as forceful as his Fugues, or perhaps he couldn’t stop the intensity after 90 minutes of entangling music.

Yet the original Bach, and Dame Myra’s arrangement were both gentle filigrees of devotion. Mr. Trifonov’s performance was not so much adoration as a peremptory Lutheran command.

We didn’t need encores, I felt, but Mr. Trifonov is like George Gershwin: nobody can stop him from playing. In this case, I confess to not recognizing a single work. The generous New York Philharmonic producers (Mr. Trifonov is the pianist-in-residence) informed me that they were written by Johann Christian, Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel.)

A Bach-to-Bach-to-Bach tribute for the sons who colllated the messy pages of Dad’s Art of the Fugue, after his death. Methinks, in doing their filial duty, they would have been astonished and proud of this young Russian turning mere notes into transcendent power.

Harry Rolnick

|