|

Back

The Universe According to Liszt New York

Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn

09/24/2019 - & September 25, 26, 27, 2019

Franz Liszt: Poetic and Religious Harmonies: I. Invocation; II. Ave Maria; III. Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude; IV. Pensée des morts; V. Pater Noster; VI. Hymne de l’enfant ŕ son reveil; VII. Funérailles; VIII. Miserere (d’aprčs Palestrina); IX. Andante lagrimoso; X. Cantique d’amour

Adam Tendler (I, IV, V, VIII, IX), Jenny Lin (II, III, VI, VII, X) (Pianists)

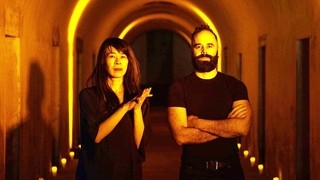

J. Lin, A. Tendler (© Kevin Condon)

“Limited in his nature, infinite in his desires, man is a fallen god who remembers the heavens.”

Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-1869)

“I did not compose my work as one might put on a church vestment... rather it sprung from the truly fervent faith of my heart, such as I have felt it since my childhood.”

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

After a few years of crypts and graveyards, we no longer find these venues a novelty, Andrew Ousley’s “The Angel’s Share” and “The Death of Classical” surveys the darker parts of earth, and transmogrifies them as comfortable as Lincoln Center and BargeMusic.

What has indeed improved is that the music is more attuned (so to speak) to the circumstances. And last night (along with tonight and tomorrow) we had the feeling that Franz Liszt, with his emotional, contradictory, always passionate attitude to composition and performance, would have approved the crypt of Green-Wood cemetery as he would the Grand Salons of Europe and the Intimate Boudoirs of obscure princesses in even more obscure Royal States.

(And f.y.i., yes he did play music there pre– and pro– his...uh, other performances. I believe Mr. Sinatra offered the same self-adoring testicles...er, testaments to his artistry.)

So Liszt’s Poetic and Religious Harmonies was a triumph of music in just the right place.

Albeit with three small admonishments.

One was a light problem. Literally. On opening night, the concert was being filmed, and while the cameras were judiciously placed, that meant a glaring fluorescent illumination in the crypt. Not the more subtle simulation of candlelight.

Second was a Sin of Omission. In a printed program , which notated poems by Alphonse de Lamartine and a description of creator-curator Andrew Ousley’s raisons d’ętre for the venues in graveyards and crypts, we had not a single mention of either artist.

That was absurd, though Jenny Lin has a both familiar face and fingers. She is one of Philip Glass’s chosen performers for his Etudes, an artist who can handle Mompou and Earl Wild, and diverse others from most centuries.

Adam Tendler was new to this listener, though his gallant physical presence alone could have replaced the persona of Franz Liszt in Ken Russell’s Lisztomania. The winner this year of Lincoln Center’s “Emerging Artist”, he has recorded all the Bachs, as well as John Cage, George Crumb, Charles Griffes and...

You get the idea. This man gets around the keyboard and around diverse composers as easily as he essayed these ten Liszt works.

A more rudimentary error, in my opinion, is that the complete set of Poetic and Religious Harmonies was separated with an intermission. Fifteen minutes of shmoozing and urinating between Pater Noster and A Child Awakening.

Now nobody would think of bisecting Beethoven’s Ninth or Mahler’s Eighth or–the one comparable work to the Liszt–Messiaen’s two-hour-long Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus. The full-crypt audience had either driven in, taken the subway, or crossed the River Styx by tipping Charon the Ferryman to row Brooklyn-wise, and they deserved the rare opportunity to hear the complete Liszt emissions, not a concertus interruptus.

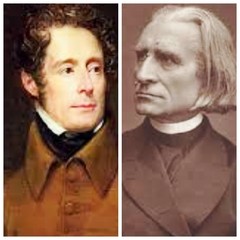

A. de Lamartine/F. Liszt

Granted, most of the ten works had been composed over the years, put together like an anthology, and bound with the mottos and poetry of Lamartine (himself a far more orthodox Catholic than the composer). But it essential, I feel, that the moods, embracing religious, archaic, romantic, naive, needed a unity, even when the emotions contradicted each other. When church bells echoed childish prayers, when the horror of the dead was surrounded by blessings and a prayer.

That aside, this was masterly playing by both Messrs Tendler and Lin, who alternated their selections. No errors were made, nothing idiosyncratic was offered, each work was both a world unto itself–and part of Liszt’s multifarious universes.

Mr. Tendler announced the doxology with a heroic Invocation, hardly great Liszt but appropriate for the whole performance. Ms. Ho continued with two more tender works. Not because of her gender, of course, The strongest, most muscular and continuously great music came from Ms. Lin’s work with Funérailles. I granted this was partly because of its familiarity. But also because Ms. Lin gave a subtle yet increasingly muscular presentation until the end, when the Crypt was literally resounding.

The other works, both familiar and relatively obscure, both brilliant (the mystical Benediction) and second rate (a free arrangement of Palestrina) made their way through the evening. One strange occurrence was the finish of the aforesaid Palestrina. Whatever Liszt’s piano, one doubts that it had the resonance of last evening’s Yamaha. Thus, for the last sustained–very sustained–last chord, the piano offered not only overtones, but virtually every note which had been played for the past 30 seconds.

So if it sounded like Henry Cowell, that was a minor technical glitch.

Otherwise, this was a splendid recital by a pair of splendid players. Was Liszt’s music mystical? Mysterious? Did one feel both religious and poetic? Religious or amorous? That didn’t matter. The old-fashioned judgment that Liszt was bombast has long been overruled. Here, one knew that this most singular composer, wrapping Baroque and Romantic and (in his last compositions) atonal, was given his due. After the Benediction and Miserere, before the torchlit procession through the cemetery, we had to utter our own “Amen.”

Harry Rolnick

|