|

Back

The Infinite Beauty of Pure Energy New York

David Geffen Auditorium, Lincoln Center

04/24/2019 - & April 27, 30, 2019

Thomas Larcher: Symphony No. 2 “Kenotaph” (American Premiere)

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 4 in E Minor, Opus 98

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Semyon Bychkov (Conductor)

T. Larcher

“Energie is the operation, efflux or activity of any being: as the light of the Sunne is the energie of the Sunne, and every phantasm of the soul is the energie of the soul.”

From Platonica: A Platonicall Song of the Soul, by Henry More (1614-1687)

A century ago, musical savants declared that Jean Sibelius was the last symphonist, and (albeit numerous exceptions) they were right. Last night, Thomas Larcher’s Second Symphony was given its American premiere, and one realized that the standard symphonic structure is alive, is well, and is definitely thriving.

Mr. Larcher is perhaps Austria’s most renowned composer, and for good reason. He is meticulous, imaginative, he has the orchestral colors of a Tintoretto and the musical architecture of a Christopher Wren. More essential, his “Cenotaph” symphony has the kind of infinite energy which allows one to almost visualize the energy of a solar system or two.

The composer explained before the performance that his work was in memory of those tens of thousands of refugees from the Middle East and Africa who had drowned in the Mediterranean. And while this was truly touching, such thoughts were supplemental to his original title as a Concerto For Orchestra.

Each of the four classical movements (Allegro, Adagio, Scherzo, Molto Allegro) had a dynamism which defied words. The piece opened with a fierce whacking sforzando chord, continued with a whirlwind of lows and highs, loud dissonance, soft consonance, fanfares and reveilles, chorales and Mahler-style ultra-romantic melodies. Yes, one wanted to understand a structure, but the energy of this movement defied rationality. Naturally, he out all the stops for his massive percussion section–oil drums, mixing bowls, thunder-sheets, paper and sizzle cymbals–but he also created a euphony with a prepared piano, an accordion (which I didn’t hear), harp and celesta.

We had a solo viola, we had a beautiful violin solo (repeated in the finale), and we had waves of sound, some kitschy-catchy tunes and the most vivid patina of colors.

(As well as the grotesque audience-coughers, who managed to destroy the end of each movement.)

The Adagio was relatively quiet, it had great vistas of color, it had possibly quotes from Mahler, and gave way to a raucous equally incredible scherzo. It was loud, whacky, primitive (the way Picasso is primitive!), and at the finish, Mr. Larcher decided to have us forget the whole thing: a pair of clarinets tootling a short lullaby that could have come from Brahms. (Destroyed again by the chorale of coughers.)

As one might imagine, Mr. Larcher never let the finale go without more luscious waves of orchestra, more percussive marching, more high Shakespearean comedy and tragedy following each other until the funereal last measures.

At the very least, this was 35 minutes of the most intense entertainment. Not Poulenc-Milhaud entertainment, but the show of...well, one must use a Kafka title from his Amerika: the mythical state-wide “Nature Theater of Oklahoma”.

Mr. Larcher presented a panorama which was so gorgeous that its first-hearing indecipherability was of no interest. This Second Symphony was not music’s usual metaphor for energy. It was energy itself.

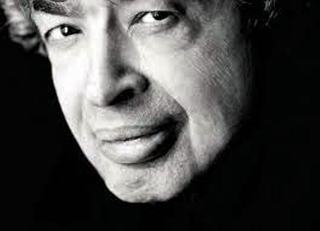

S. Bychkov

Semyon Bychkov conducted the world premiere of the Second Symphony as well as the American premiere last night. I was warned once not to write about a conductor’s physical movements, but Mr. Bychkov is so dynamic, so precise and last night was so meticulous in guiding complex Thomas Larcher’s work that one had to give him extra credits.

After the intermission, Mr. Bychkov conducted one of Mr. Larcher’s predecessors, the Brahms Fourth Symphony. One must also give credit to Brahms. Even without accordions, slide whistles (large and small) and tuned bongo drums, he managed to create a monumental work.

Mr. Bychkov had one idiosyncratic moment–stopping the Philharmonic for a measure or two at a first-movement climax–but otherwise taking this well-deserved favorite to its grand, no-holds-barred climax.

Yes, most of the audience went out with those last chords in their minds. This writer was still obsessed with the violent first notes of Mr. Larcher’s Symphony and trying to resurrect the final-measure whisper of lament.

Harry Rolnick

|