|

Back

Strings of Another Era New York

J. Pierpont Morgan Library

04/23/2019 -

Joseph Haydn: String Quartet in C Major, Opus 20, No. 2

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 1 in F Major, Opus 18, No. 1

Diderot String Quartet: Johanna Novom, Adriane Post (Violins), Kyle Miller (Viola), Paul Dwyer (Cello

K. Miller, J. Novom, A. Post, P. Dwyer

(© Jennifer Toole & Tatiana Daubek)

“Good music is very close to primitive language.”

Denis Diderot (1713-1784)

The Diderot quote above is not a vilification. As one of the truly great Age of Reason polymaths, Diderot doubtless was fascinated by philology as much as music. For his Encyclopedia, he had enlisted Jean-Jacques Rousseau to write about music (Rousseau himself had composed a charming pastoral opera), and Diderot was not only a philosopher, but wrote one of the first surrealistic novels, Jacques the Fatalist, which is still terrific reading.

Which brings us to the Diderot String Quartet, named after Diderot, the way the Emerson String Quartet honors the American philosopher. Yet these four young fiddlers, from Oberlin and Juilliard, took more than the name. Their instruments are based on 18th Century violins, violas and cellos, approximating the dates of Diderot himself. The sounds can be flat or blurred at times. But in the two pieces played here, one could feel, without imagination, that Haydn and Beethoven would have recognized what they had heard in their own minds.

And for that alone, the Diderot String Quartet was worthy of note. Or notes.

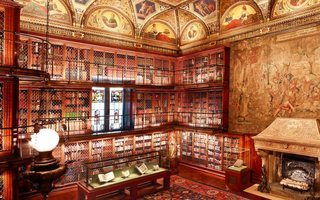

The J. Pierpont Morgan Library (© The Morgan Library And Museum)

Yet one must be honest. The second motivation to brave the rush-hour subways was to saunter into one of the most exquisite rooms in New York. The Morgan Library boasts a huge Flemish tapestry, which had hung in one of Henry VIII’s palaces. The centuries-old ivory-colored fireplace mantel is an original. Above are “medieval” paintings commissioned by Morgan, as well as a rare rare library of Bibles, gazetteers, atlases and splendidly covered first editions, as well as temporary exhibitions, like the thousand-year-old psalters shown last night.

Such an overwhelming assemblage might intimidate any musicians, but the Diderot String Quartet took it all in their stride, even taking time out to explain the intricacies of their ancient-style instruments, though the technical minutiae were not totally significant to this non-string player. Briefly, no synthetic materials for the strings, no chin rests, shorter bows and–18th Century style–all standing save for the cellist.

Here, though, the Late Baroque instruments did not result in the strings being played close to the chest. All was bowed and played, to my eyes, like modern instruments. And the results were fulfilling for their historical value.

Aesthetically it was a mixed bag. At times, when all four instruments were rumbling in the lower ranges, one heard an inevitable blurring, a lack of articulation. (And because of the Diderot’s expertise, that had to have been due to their instruments.) Alternatively, when violinists Johanna Novom and Adriane Post were playing together in thirds, during much of the Haydn quartet, the sounds were like those of early opera. Flute-like, highly lyrical, with voices like Mozart sopranos dashing up and down the scales.

The best part of the acoustic problem was that, having visited the concert hall of Haydn’s Esterházy-kastély in Hungary, I realized the dimensions there were basically those of the Morgan Library, with equally intimate coloration.

Those colors were so well expressed in the Haydn C Major Quartet, where all the instruments were given solos, and where Mr. Dwyer’s cello had a chance for the wildest figurations. One could hear so well how Haydn, in one of his joking moods, gave the continuo part to the viola, and how Mr. Dwyer’s solo later gave grist to the two singing violinists.

These first three movements were played with a contentment which wasn’t courtly, wasn’t stylish, but gave a chance for each soloist to enjoy a few moments in their own sun (yes, all the Opus 20 quartets are called “Sun” Quartets). And in the second movement, Ms. Novom’s solos again had an operatic cantabile.

Equally, while not all moments were so transparent, one knew that Haydn’s expertise in counterpoint was as close to Bach as possible, including the last movement fugue. Not with Bach’s usual solemnity for sacred form, but a fugue resembling a gig! Obviously this was another Haydn game, and the Diderot group played it with fitting abandon.

The Beethoven F Major Quartet was a different work entirely, written three decades later. I have heard it played with more muscularity, more subtlety in the alleged “Romeo and Juliet Tomb Scene” Adagio. But the Diderot String quartet gave a rendering of utmost virtuosity, with the same shimmering colors in the two violins.

For those who appreciate the finesse and care which Beethoven gave to his finales, the Diderot group did not rush along in the Allegro finale. They gave it a relatively relaxed, always melodic tempo.

The year he wrote it, Beethoven was beginning what would become his torment of deafness. With this first quartet, he was still in Haydn’s beneficent shadows, and the performance here gave both comfort and joy.

Harry Rolnick

|