|

Back

Dreams of a Schubertian Meadow New York

Isaac Stern, Auditorium Carnegie Hall

03/08/2019 -

Nico Muhly: Liar: Suite, from Marnie (New York premiere)

Felix Mendelssohn: Piano Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Opus 25

Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 9 in C Major (“Great”), D. 944

Jan Lisiecki (Pianist)

Philadelphia Orchestra, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, (Conductor)

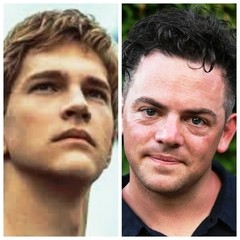

Y. Nézet-Séguin

Two of the three greatest Ninth symphonies were played this week in Carnegie Hall. Excluded was Beethoven’s Ninth, that Promethean work offered to us mere mortals. Mahler’s Ninth was for arcane metaphysicians, symbolists and poets. Finally, Franz Schubert’s Ninth, was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra last night under one of their great great conductors, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin, gave the gorgeous homage to mountains and streams, to grassy swards and sky, and all which Nature afforded to the composer, in his Austrian countryside and his soul.

Perhaps it was such a staggering performance because two nights ago, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra was so unusually shaky, while each consort of the Philadelphia Orchestra was at the pinnacle of their sound quality.

In fact, for the first measure French horn solo, I almost flinched, wondering whether this might be another Vienna catastrophe. But no, First Horn Jennifer Montone gave stentorian sounds throughout the Symphony, as did the other wind soloists.

One need not speak about the strings of the Philadelphia Orchestra. They have power when necessary, but the voices are velvet, the perfections of the ensembles always endearing.

And now we come to their conductor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Having left his native Montreal, with its Gallic/British hybrid populace and ersatz bagels, he–like so many iconic conductors in Philadelphia–has preserved those breathtaking sounds, augmenting them with breadth and lyricism.

In fact, during the introduction to the Ninth, one realized immediately why Mr. Nézet-Séguin is now conductor of the Metropolitan Opera. That opening played like Schwarzkopf singing Schubert lieder.

After that, Mr. Nézet-Séguin took the orchestra for a ride which was swifter than usual, but in which he offered a God’s-eye view of Nature itself. No, he didn’t turn this into a whirlwind: he gave it just enough pulse and persistence to make the Symphony initially lovely–and then give us some surprises.

In the first and second movements, Mr. Nézet-Séguin accented descants which are rarely heard. The strings played along dutifully, but he allowed those “accompanying” winds to play their own melodies. In the so-called “walking” second movement, Mr. Nézet-Séguin allowed us to see Schubert hastening over the hillocks, jumping over the streams, and take a dreamy rest.

For the third movement, he realized that Schubert–like Dvorák–was never able to resist dancing and singing, in even the mightiest of symphonies.

This was not an adventurous Ninth, nor did it ever seem to have a “heavenly length.” Heaven is perfect, heaven doesn’t need to move. Yes, Mr. Nézet-Séguin moved the symphony through its paces to the finale, but one became so enamored of the sounds and the pacing that the marvelous Beethoven Ninth quote seemed quite in place. As if Schubert didn’t want to quote Beethoven, but simply felt that Beethoven’s woodwind measures would fit in oh so nicely.

And in those final moments, with trombones and horns, with percussion and strings, Mr. Nézet-Séguin stopped us wondering about his pacing. He simply let those grand climaxes–that music which was the apotheosis of Austrian Adoration of Nature–soar to the top of Carnegie Hall.

I doubt whether he would dare to give an encore, but didn’t bother to stay. I needed Manhattan’s fresh cool Friday night air, so exited Carnegie Hall, strolled, sauntered, walked at an Andante con moto pace downtown towards my home.

J. Lisiecki/N. Muhly

Obviously this was not the whole program. The evening began with a most curious piece by that most talented composer of our generation, Nico Muhly.

Marnie was originally a novel, then turned into a good (if not perfect) Hitchcock film which dealt somehow with mental problems and kleptomania. Mainly, though, no matter what Hitchcock did, it was Pure Movie, pure eccentricity and Pure Unexpected Angularity.

Mr. Muhly morphed Marnie again, this into a well-reviewed opera at the Metropolitan. I didn’t see it, and it was probably very different from the film, so my memories of the Bernard Herrmann music could stand.

The confusion came with an 18-minute suite (Liar) with music from the opera. The Program Notes gave more than a complete synopsis of the suite, told how Act I came after Act II, and how different instruments played different characters, and they all were in different scenes.

Mr. Muhly is a master of orchestration, but I frankly couldn’t make any sense of Liar. Simply because I wasn’t sure whether to follow the story Straussian style, or hear it as pure music, or pretend that it gave an idea of the film itself. It was probably quite good, but my shortsighted confusion precluded appreciation or enjoyment.

In a program fit for one conductor and one composer, we needed only one soloist to balance it out. Jan Lisiecki was indeed a fantastic soloist, with fingers so swift that he hardly needed either orchestra or conductor.

On the other hand, Mendelssohn’s First Concerto was made for this kind of dexterity. He started off with a bang (no, not the right words: he started with smooth and faultless high-powered scales), and finished the same way.

As a technician, Mr. Lisiecki was unparalleled. As an artist, he let us take a glance into his mind only twice. First, with a simple, almost Mozartean Andante, before zooming into the Presto finale.

Second was his short and lovely encore. This was Mendelssohn’s Venetian Gondola Song. Where the Concerto gave us digital thrills, this encore was Mendelssohn the painter, and Mr. Lisiecki gave us gentle strokes and a nuanced canvas.

Harry Rolnick

|