|

Back

Merry Shepherds of Myth and Melody New York

Katonah (Caramoor Center for Music and the Arts, Venetian Theater)

07/22/2018 -

Georg Frederic Handel: Atalanta, HWV 35

Sherezade Panthaki (Atalanta), Amy Freston (Meleagro), Cécile van de Sant (Irene), Isaiah Bell (Aminta), Philip Cutlip (Nicandro), Davóne Tines (Mercurio)

Chorus: Elizabeth Bates, Jolle Greenleaf (Sopranos), Patrick Fennig (Countertenor), Jacqi Kwiatek-Horner (Mezzo-Soprano), Donald Meineke, David Reese (Tenors), Paul An, Dominic Inferrara (Basses); Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan (Conductor), Jolle Greenleaf (Artistic Director)

I. Bell, C. Van de Sant, P. Cutlip, A. Preston, S. Panthaki

(© Samuel A. Dog)

“You have taken too much trouble over your opera. Here in England that is a mere waste of time. What the English like is something they can beat time to, something that hits them straight on the drum of the ear.”

Georg Frederic Handel to a composer who wanted an opera to be performed in London

One vexing question about Handel’s 1736 pastoral opera, Atalanta, “drama with music,” based on Belisario Valeriani’s Caccia in Etolia:

During the 140 minutes when four real and ersatz shepherds were fretting, stewing, recriminating, loving, hating and finally joining together in holy matrimony, where the hell did all those sheep wander off to?

A foolish question, more appropriate for Little Bo Peep. The sheep of Atalanta were more Ovid than ovine. The shepherds of Atalanta lived in an Arcadian fairy-tale world going back to Theocritus and Hesiod and Virgil, where “fawns and dryads” (from a chorus in Atalanta) frolicked, when Kings and Princesses forsook their Royal Titles to gambol on lawns and meadows identical to the lawns and meadows of Caramoor. And where Shakespeare would have scorned the stories told in these pastorales.

But what did Handel care? His inspirations were as sumptuous as his legendary meals, his commission to write an opera celebrating the wedding of two Royals was an invitation to write for a prized castrato, invent stage machinery which an 18th Century Penn and Teller would envy–and to compose endless tunes, a duet or two (Rosenkavalier would be inspired by the love duets of two female voices), a few choruses and overtures for drums and trumpets.

N. McGegan (© Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra)

Exactly what the Caramoor Festival–and conductor Nicholas McGegan–re created to do.

Mr. McGegan is always welcome in New York, his personality and conducting skills double-treats. But he is best known for music of the Baroque, and his San Francisco-based Baroque Philharmonia was brought over to Caramoor for this occasion.

Sitting on the side of the stage, the strings, oboes and long-armed Baroque trumpets were conducted with ardor, passion and fun. Mr. McGegan has performed this Handel pastorale several times, even gave it the only recording. He loves it, and he made the audience love it–at least for the First Act–with equal passion.

True, many in the audience felt that this two-plus hours work was...er, longish. Handel and his audience would have scorned them. His operas were usually close to four hours long, with extended ale-and-sausages intervals, and nobody complained. Yet during the second act, one inevitably felt that the arias, the short recitatives and plotting mishaps did repeat themselves.

In the 1735 though, nobody cared. They were looking for vocal improv, and no doubt the famed young castrato Giocchiano Conti sung his heart out (Handel gave him chances to dance on a high C), probably repeating his melodies several times. Obviously the original Atalanta had equal opportunity to flail her vocal chords out, all of which should have impressed 18th Century audiences.

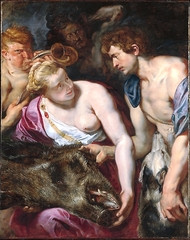

Peter Paul Rubens’ Atalanta and Meleagro

The original production also had tons of stage machinery, needed for hunting the wild boar (see Rubens’ picture above), flying Mercury out to the grand finale, and–for the final epithalamiom–real 18th Century fireworks.

At Caramoor, we had none of this. The “costumes” were present-day dress, there was no staging, only a few chairs, and no scenery of any kind. An opera like this, though, needs more than a scintilla of Baroque/Arcadia landscape or dress. Having those splendid instruments of the Baroque Philharmonia is no replacement for some pantaloons, a few wigs, perhaps some fake wings on Mercury. Those small bits inspire us to a willing suspension of disbelief.

Even better, this is the kind of pastoral opera which needs the Regency-manicured Caramoor sward to make its mark.

Fortunately, Mr. McGegan inspired singing which would have made Handel proud. The low-voiced males were minor, but both superb. Philip Cutlip as Irene’s father was stately and resonant, his First Act aria resembling a Handel oratorio declaration. And while we had to wait for Davóne Tines’s literal deus ex machina, his lengthy aria to the greatness of Great Britain was colorful and piercing. Tenor Isaiah Bell was fine as Irene’s betrothed–but competing with two virago females, naturally was difficult to overcome.

One was contralto Cécile van de Sant in the very nasty role of Irene. Carrying a parasol, she could have been a Broadway coquette, but far more unkind, teasing her poor lover (she thinks he wants her property), but singing up a storm when needed. The statuesque Amy Preston started a bit shrilly in the opening aria (the only aria which has made it to the concert stage), but at her best–in a duet with Sherezade Panthaki as Atalanta–we had a work amongst the very best ever written by Handel.

Then we come to Ms. Panthaki herself. While shorter than the spindly Ms. Preston, this Atalanta was athletic, rugged, the goddess-hunter, the sister of Diana, Superwoman and Gloria Steinen. And wow! Did she sing those Handel arias like she would tear down the Venetian Theater tent!

Her songs, her trills and rolls up the scale, her (possible) improvisations were more than bel canto. These were bellissimo canto, vibrating across the mythical Arcadian meadows out to the stunned audience.

Still, one does not enjoy meditating on post-opera home-life of mild King Meleagro and raging Princess Atalanta, (“You want me to do the dishes?” she asks. “I...don’t...think...so, Bro.”)

In the short (and for some, the long run), this production was mainly a delight. The sous-titres helped those who hadn’t read the synopsis, Mr. McGegan’s orchestra played at a rompish tempo. And for those who could Handel an Arcadian mood for three lengthy acts, the opera was crisp, it had a patina of the bucolic, and the singing was frequently glorious.

Harry Rolnick

|