|

Back

Explosions and Exotica New York

Weill Recital Hall, Carnegie Hall

06/01/2017 -

Yukiko Nishimura: Ten Etudes

Kouji Taku: Variations on a Theme of Poulenc

Yoshinao Nakada: Piano Sonata

Jacques Ibert: Histoires

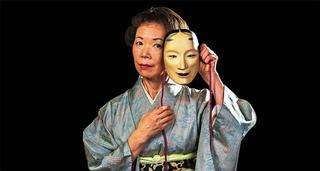

“Key Pianists”: Sara Davis Buechner (Pianist), Yayoi Hirano (Mime, mask-carver)

S. D. Buechner (© Courtesy of the Artist)

“Where have you gone, Tōru Takemitsu?/A nation turns its prosp’rous eyes on you./Woo woo woo.”

Simon and Garfunkel, Mrs. Robinson (Revised)

Put another way where are those dainty haiku, those koto warblings, those gracious musical honorifics and hymns to the sun-god? True, Japan’s arts have always had a sense of violence beneath the delicate exterior (Kurosawa’s films makes those of his friend Scorsese look like Little Women). Yet not until last night did one hear the explosive sounds of contemporary Japanese composition.

The purveyor of this music was the astonishing Sara Davis Buechner, already renowned for her recordings of Busoni, Gershwin, and rare 19th and 20th Century concertos and solo music. She and her spouse spend half their time in Philadelphia (she is on the piano faculty of Temple University) and half in Osaka, where she is an linguist and ardent searcher for astonishing music.

It was in that latter role where she made the dainty Baroque walls of Weill Concert Hall quiver and throb, with music that had more to do with Scriabin than Takemitsu.

Yet even in music which could have erupted out of New York or Europe, the composers themselves were unique. The strenuous Ten Etudes were written by diminutive self-effacing Yukiko Nishimura, who was in the audience. A set of Poulenc variations was written by Kouji Taku, who reversed the Brahms lifestyle. At the age of 60, he reversed his status as an esteemed composer and teacher and departed for a saloon, where he could play show-tunes all night.

Finally came the tragic case of Yoshinao Nakada, an ex-Kamikaze pilot who disgraced himself by coming back alive from a suicide mission. It was his agony which he depicted in a gripping Sonata.

Nothing was simple in the Ten Etudes. The names may have smacked of japonaiserie (“Snowy Skies”, “Daydreaming”, “Harvest Moon”), but to accomplish these suggestions of pictures, Ms. Buechner needed at least four hands. She crossed and re-crossed them, played a chattering toccata in Fanfare, and took a melody which could have come out of Schumann’s Children’s Pieces in “Hide-and-Seek” transforming it into a whirligig of trickery. Two works were written for solo hands (and “Rock Candy” sounded like at least three hands playing) and ended with an explosive “Harvest Moon.”

Ms. Buechner had these techniques down pat. Nothing seemed to faze her, and–most essential–she never exaggerated her skills. The music was organic rather than orgasmic.

Kouji Taku’s variations on Poulenc’s popular first Mouvements perpétuels almost made the original theme disappear with his tango, samba and bluesy sections. Yet those first measures of the Poulenc always made their way into the music, and Ms. Buechner knew how to balance the complex sounds so we could hear the original cells somewhere in here.

In all three works (and mainly the Variations), the composers showed their not-ironic love with cocktail music. They never shmaltzed it up, but could always quote Sinatra/Julie London styles when necessary. Yet the most interesting was in the “haunting” Adagio of Yoshinao Nakada’s Sonata.

Ms. Buechner’s adjective is put in quotes, because I found this movement the least impressive. It was supposedly the composer’s honoring of the great Meiji flowering of Japanese arts, but the remembrance of things past–akin to a Mahler/Berg remembrance of old dances–seemed sentimental at best. Certainly compared to the tempestuous Scriabin-like finale.

For the opening movement, one had to go back to the first song of Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen the night before. In both movements, we had sentiment leading to stridency, mooning leading to military. In both, a childish tune led to explosions of passion. Mr. Nakada’s, though, was based on his singular experience in the war. Those unaware of that would still find both works stunning.

Hirano Y. (© Langarapm.com)

The only non-Japanese piece became totally Japanese, thanks to the guest artist, the mime-actor-dancer-maskmaker, Yayoi Hirano. Jacques Ibert was as French as Poulenc, but his travels gave him an exotic touch to his music. Added to this, the French love of “typical” Japanese miniatures. (The only paintings in Ravel’s house are Japanese.)

Thus the Histoires were easily complemented by the wondrous acting and masks of Ms. Hirano. In fact, so visual, so graphic, so literally moving were her body and mask for “the giddy girl”, the old beggar-woman, the donkey (I couldn’t believe those movements), and her clawing at the invisible “crystal cage” that one couldn’t quite concentrate on the pianist.

One doubts whether Sara Davis Buechner would have been affronted. The purpose of “Key Pianists” is to allow artists to present rare music which they feel is best for themselves. Ms. Buechner wanted this music to be heard. And whether fortissimo clangs, or the tiny wooden-knocking mechanics of Ms. Nishimura’s “Windmill”, she created an unforgettable universe of original voices.

Harry Rolnick

|