|

Back

Bareboim’s String-and-Wind Theory New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

01/24/2017 -

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat Major, K. 297b

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 5

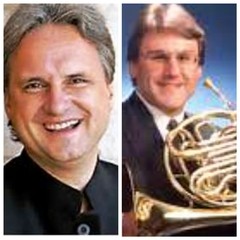

Gregor Witt (Oboe), Matthias Glander (Clarinet), Radovan Vlatkovic (Horn), Matthias Baker (Bassoon)

Staatskapelle Berlin, Daniel Barenboim (Music Director, Conductor)

M. Glander/R.Vlatkovic (© az-online.de/croatia.org)

“In her mind she could remember about six different Mozart tunes from the pieces she had heard. A few of them were kind of quick and tinkling, and another was like that smell in springtime after a rain. But they all made her somehow sad and excited at the same time.

“She hummed one of the tunes, and after a while in the hot, empty house by herself she felt the tears come in her eyes.”

Carson McCullers, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

Was that humming perhaps from the final Adagio measures of the E-flat Sinfonia concertante? Perhaps not. And anyhow, Carson McCullers’s words were Mozart music themselves. Yet after hearing this opening work from the Bruckner Symphony Cycle last night, one could well imagine it bringing tears to any eyes.

After the first five nights where Daniel Barenboim played and conducted (conducting, I might say, with as much zest as if no piano was under his hands), he was forgiven for taking a break last night and tonight. Yet his choice of this Sinfonia Concertante was questionable, since no proof exists that Mozart composed it at all.

Yet from the very first measures to the deliciously childlike variations at the end, it was sheer Mozart. Not merely the invention, but the weaving of the colours, the joy, the melancholy, that “sadness and excitement.”

The history itself is blurry. Apparently he had written another concerto, with flute, but this was lost. So the latest theory is that somebody might have taken that work and replaced flute with clarinet. Questioning the authorship of such a work, though, is a specious concern. Perhaps the answer is what Mark Twain same about the authorship of Shakespeare: “It was written by another dramatist with the same genius and the same name.”

And the same joy. In the opening movement, all four players bubble over with good cheer. The oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon take turns, as if in a wonderful child’s game, pairing with each other, alternating solos or weaving the colors in and out.

For the aforesaid Adagio, we had a joy and a problem with visiting French horn player Radovan Vlatkovic. His runs up and down the instrument could have come from a violin, seamless, faultless. Yet the balance for this so sensitive movement was off, and when playing in ensemble, the horn overpowered the other instruments. Mozart’s love for the winds in consort was so great that he might have told Mr. Vlatkovic that his own greatness was equaled by the other players.

The finale took the most childish theme Mozart could have written, but the variations here gave a chance for each player to do his best. The last cadence of the theme is almost a cliché, a puerile ending for each section. But none of the players took it seriously, and the result was a romp.

Romp is hardly the word to use for Mr. Barenboim’s production of the Bruckner Fifth Symphony. One would like to use the word “revelation” or “vision” or courageous...or any word which could describe one of the most mightyof the Bruckner symphonies.

Oh, yes, others might prefer the Eighth or surmise that he never wrote an ending to the Ninth because nothing could surpass what he had written.

But when it comes to mightiness, that Fifth, with its ear-piercing chorales, its Beethoven-like fugues, and the most climatic of all climaxes, beats all.

As did Maestro Barenboim give it all the thrust and parry, the never-ending tension, those gorgeous moments for which the Staatskapelle Berlin is so attuned.

G. Witt (© Courtesy of the Artist)

Two of the four soloists in the Mozart, oboist Gregor Witt and clarinetist Matthias Glander, are First Chair players in the orchestra, and their own solos–especially Mr. Witt, whose oboe theme in the second movement was the germinal movement for the whole symphony. In my score, that keening tune is marked “very slowly”, but Mr. Barenboim gave it a faster lilt, which seemed to fit in well.

Yet it wasn’t the triumph of the brass or winds or those two remarkable timpani players (okay, they were standing up, but still mesmeric). It was the Staatskapelle Berlin strings, leading the fugues with clarity, with tension. It was the strings in the introduction to the first movement–and their great structural foundation for the grand ending, which gave this work such a grandiosity, such a...well, perhaps satisfaction is too ordinary a word.

What Mr. Barenboim did was give a sense that this Symphony was of a single movement. We had pauses between all four movements (with enough space to make the emphysema-stricken audience loudly expectorate their spittle), but the conductor offered more than repetition of themes for unity. The entire work breathed a both structural unity and breathless emotional wholeness.

Harry Rolnick

|