|

Back

Cosmic and Human Nobility New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

05/20/2012 -

Anton Webern: Five Pieces for Orchestra; Opus 10

Franz Schubert: Symphony Number 4 in C minor (“Tragic”)

Johannes Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major

Christian Zacharias (Piano)

Bamberger Symphoniker, Jonathan Nott (Conductor)

J. Nott (© Askonas Holt)

A springtime-sunny New York Sunday, and my druthers were for roses blooming, chocolate-mint ice cream, and parks filled with spaniels, squirrels and lovers. Maybe I could tolerate Brahms’s Third Symphony but certainly not his autumnal Second Piano Concerto in the middle of this bucolic afternoon

Yet that was the concert, and that was my duty. And after all, with Christian Zacharias playing the Brahms, while the music was inappropriate for the meteorology, listening would hardly be a chore.

Prior to the Brahms, though, two other attractions had brought a fair audience to Avery Fisher Hall yesterday. The Bamberg Orchestra has, amongst German ensembles, a stunning reputation for the most elegant playing. Even in a country suffering the after-pangs of von Karajan grandiosity, Bamberg has a singular reputation, not least of which is due to their long-time British conductor, Jonathan Nott.

Jonathan Nott has been reputed as a great conductor of 19th Century music, two works of which he conducted yesterday. But he has also been a staple conductor of Pierre Boulez’ Ensemble Intercontemporain. And the opening six minutes were devoted to one of the great works of the last century.

Conductors are loathe to schedule Webern’s Five Orchestral Pieces, simply because some audiences thing they aren’t getting their money’s worth. (I once saw conductor turn at the end to the baffled audience, and without a word of excuse, simply repeat the music.)

But listening to it, or following with a score, the Five Pieces, to an open mind, have a cosmic beauty. They are not “aphoristic” or “bagatelles”, as some writers say. Instead, they follow–as music should follow–no human logic. A century ago, when written, they might have been called “molecular”, but this overstates their presence. Today, each pianissimo single note, fleeting chord, single instance of a real chord, could only be called pre-organic.

The way Jonathan Nott conducted, with utter transparency, with balance and sensibility, the notes were like quarks or subatomic particles. We could hear the note, but it would disappear, perhaps transformed, but likely going down its own wormhole coming out in another guise

As far as I was concerned, Mr. Nott’s Five Piecers was the closest I could come to a universe which initially seems unconnected and chaotic. Yet each spatial chaotic moment is still linked (in its own language), both in color, tone, and duration, with everything else.

It can be an amazing experience. And when it was finished, Mr. Nott could have waited for the polite applause. But he is too clever a conductor for that.

Following those Webernian sub-atoms, within two seconds of the final soft cello and high celesta, the orchestra coalesced into the language of another Austrian, Franz Schubert.

The transformation was a ray of light into the wonders of the dark universe, and the Bamberg Symphony made the most of it. The work is called “tragic”, but after the introduction, it skirts on a more equatable mood.

If I could choose a single section exemplifying the finesse, the ineffable balance of the Bamberg Symphony, it would be the Trio of the consciously bumptious third movement, this played with utter harmony and light-fingered joy.

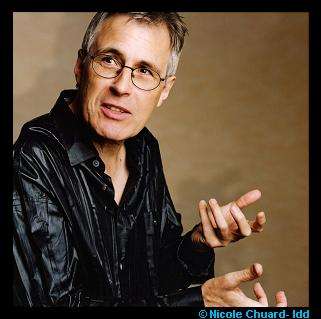

C. Zacharias (©Nicole Chuard-IDD)

After the intermission (where, standing on the second-floor balcony, I pretended to hurl Webern’s notes on the passersby below), Christian Zacharias came out to play one of the most formidable concertos of its time, the Brahms Second. I have heard it played with greater vigor, muscularity, and seriousness. But Mr. Zacharias gave the work that rarest of honors, nobility.

Nothing was pulled to exaggeration. The scherzo was more blithe than playful, the slow movement never tragic but autumnal and tender. (I was reminded of Keats’ “season of mists”.) The finale could well be ersatz Hungarian, but one had to listen hard, for this ending was played with a those so rare words, modesty and grandeur.

Mr. Zacharias, with all his great virtuosity, simply let the music sing for itself, and for that alone, the concert had both cosmic and very human nobility.

Harry Rolnick

|