|

Back

Good, Better, Zest New York

Le Poisson Rouge, Bleeker Street

04/09/2012 -

Domenico Scarlatti: Sonatas K. 64, 9, 72, 132, 29

Claude Debussy: Excerpts from Preludes, Book I: “Danseuses de Delphes” – “Le Vent dans la plaine” – “La Fille aux cheveux de lin” – “La Cathédrale engloutie” – “La Danse de Puck” – “Minstrels”

Jean Wiener: Blues

George Gershwin: The Man I love

Maurice Ravel: “Five O’Clock”, from L’Enfant et les Sortilèges (Arranged by R. Branga)

Clément Doucet: Chopinata

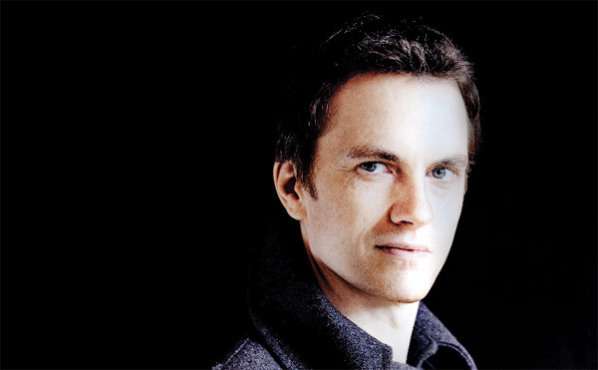

Alexandre Tharaud (Pianist)

A. Tharaud (© Virgin Classics)

“I would like to speak to you about Debussy,” said the boyish Frenchman sitting in front of his attentive audience at Le Poisson Rouge last night. “But I would rather play the music.”

Alexandre Tharaud, in this atmosphere, was magically attuned to his listeners. He can play, on record, Berg and Schubert and Ravel with the best of them. But in Le Poisson Rouge, artists are informal and ingratiating, if seldom incandescent. And in this atmosphere, the 43-year-old pianist was in his element.

His choices of music were appropriately light for the most part. (In Debussy’s “Engulfed Cathedral”, a cell phone was heard, but nobody seemed to care.) The composers were all Mediterranean. (Even his Bach encore was a transcription of Benedetto Marcello.) And these choices, as well as his engaging ‘tween music words, were perfect for his most nimble fingers.

Mr. Tharaud introduced the program by confessing that he “loved” Baroque music. But his choices were not the usual Couperin and Rameau–about whom he shares a crown with Angela Hewitt. Instead, he played a Baroque composer far more uninhibited, certainly more idiosyncratic than those French colleagues.

But Domenico Scarlatti miniatures never had much in common with their Teutonic (or even Gallic) contemporaries. Mr Tharaud played them with all the verve of a grand piano, not a little keyboard of Scarlatti’s time. His mind and fingers were concentrated, but digitally he took enormous pleasure as the K. 72 and K.29 went whirling around his cosmos. The inwardness of K. 132 was a bit affected–but this was the 18th Century definition of “affect”, as a mood, which started and ended with zest. Little pedal was used, for the resonance came from the delight he obviously had in playing them.

The seven Debussy Preludes were also miniatures, but obviously of a different import. Probably for a recording or a more orthodox concert hall, he might have give more gravity to the opening Greek dances. But his technique never failed him in the more difficult preludes–and the massive “Engulfed Cathedral” showed, for the only time tonight, that the acoustics of Poisson Rouge can be spacious enough to subdue both cutlery and errant cellular phones.

Before the final set. Mr. Tharaud gave a fascinating mini-lecture on the 1920’s jazz bar, Le Boeuf sur le Toit. Like Harlem’s Apollo Theatre in the 1920’s this was where le tout of artistic France attended. From Simenon to Satie to Stravinsky to Cocteau to Ravel, Paris learned about exotic music from African-Americans. And most of the composers incorporated it into their own music.

Unfortunately, Mr. Tharaud’s delicious mini-lecture was followed by mini-music which could only be called le jazz lukewarm”. A cocktail lounge version of Gershwin, a tepid excerpt from Ravel, and a medley of Chopin arranged as foxtrots. (Although pianists as renowned as Tharaud and Hamelin have this in their repertory, it could also have fit Welk and Liberace.)

Nonetheless to experience Alexandre Tharaud in the flesh instead of his numerous recordings was as refreshing at his music. The hour-long program was technically rather than emotionally challenging. But Mr. Tharaud’s personality and his fingers never ceased to offer an unfailingly uplifting lilt.

*******************************************

CODA: A Tale of Two Movies

Over the weekend , two excellent films played in New York, both of which used serious violin concerti, with vastly different results.

R. Weisz (© Courtesy of the artist)

If only to watch the volatile Rachel Weisz in a contemplative tragic role, The Deep Blue Sea is emotional and honest. Revived from a 1950’s period drama by Terence Rattigan, it is still eloquent and was played elegantly and emotionally 60 years after it was written.

My problem, as a music critic unhappily aware of background music in film, was the opening movement of Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto (in the authoritative version by Hillary Hahn). Mr. Barber’s concerto is raffiné enough, and the 1939 writing was apt enough for the post-War setting. But this Concerto must stand by itself.

The dissonances and modulations are hardly jarring in themselves. What happens, though, when the movement is behind a virtually silent first scene where Ms. Weisz attempts to show her mortification (cheating on her husband), her anger and confusion? The two emotions–a complete musical movement and a complete stage scene–jar against each other.

Great movie music should paint in silence without the obligation to listen or dissect. When “dedicated” screen-composers are at work, this works. Leonard Bernstein’ On The Waterfront), or Ligeti in 2001: A Space Odyssey are successful because a director like Kazan or Kubrick uses the music as an ”equal”, not a background.

Here, the Barber was competing with Ms. Weisz. It was unnerving, diverting, unneeded.

I was doubly aware of this because of the singular use of music in the Belgian movie, Le Gamin au vélo (“The Kid With The Bike”). The music consists solely of the first four four notes (repeated once) opening the second movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.

In the concert hall, those notes seem like an introduction for the Big Event to follow. In the film, those notes were repeated thrice, at places where we never expected them. Far from jarring, they became part of the movie’s poetry, while never seeming “poetic” or “artistic.” The Beethoven was like an off-stage voice, telling us in non-verbal terms, that something was happening beneath the surface.

And like any poetry, we will never understand what the “something” us. Only that the story, filmed in an almost naive plainness, was far greater than the sum of its parts. In the film itself, Beethoven’s mystery motto made a greater impact–in retrospect–than an entire violin concerto movement which, despite its romantic and passionate nature, had no right to be in a movie at all.

Harry Rolnick

|