|

Back

Gustav Mahler’s Unfinished Symphony New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

12/01/2011 - & December 2, 3, 2011

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 10 (Edited by Deryck Cooke, with collaboration by Berthold Goldschmidt, Colin Matthews, and David Matthews)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Daniel Harding (Conductor)

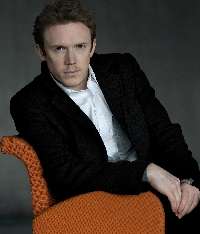

D. Harding (© Columbia Artists Management)

Almost fifty years has passed since the New York Philharmonic has performed Mahler’s “Unfinished” symphony, but one doubts that audiences were clamoring to hear it. The excuse has always been, “Well, this isn’t pure Mahler. He died before he could straighten it out, and the Deryck Cooke’s ‘finishing’ isn’t the real Mahler.”

The last might have some bearing. As Cooke himself wrote, “The body is still Mahler’s, though the clothes have been chosen for him.”

But the excuse wears thin. The truth is, that the Tenth is difficult to digest even by recordings. And those in the audience who heard it the first time (I would assume most in Avery Fisher Hall last night), while showing all due respect for an obviously meaningful work, probably found it difficult to follow.

The first movement, which Mahler finished in its entirety, opens with a long viola passage that seems to go nowhere, and it takes a long slow series of episodes to reach that nine-note dissonance, what has been called Mahler’s “scream” chord. The scherzo is no joke, the “Purgatorio” does give a picture of devils piercing and probing. But the last movement, which Cooke “assembled”, goes on and on like a prayer in a foreign language. We know we’re supposed to be in the company of a suffering genius, but the voices are too strange to assimilate.

No doubt Beethoven’s last chamber music equally confused his audiences (and ours) with its inner voices, for this was neither “classic” or “romantic”. It was Beethoven.

Mahler was neither “late romantic” or early atonal, but Mahler. To reach him in a live performance, one needs a great Mahler orchestra and a seasoned Mahler conductor.

The New York Philharmonic under Bernstein tried to reach the that kind of Mahler voice, but relatively little has been played since then. The players, while brilliant, are younger, and Alan Gilbert has become so much the master (and orchestral mentor) in an increasingly wide spectra of music that the Phil is not necessarily a Mahler orchestra.

Still, the strings of the Phil are easily up to these long long passages. The winds–which Mr. Cooke augmented–have always been good. And the marvelous “scream” chord gave the whole orchestra a chance to show its sonorities, leading with the high trumpet and going straight down to the tubas. Perhaps that sound was more an organ than an orchestra, but perhaps Mahler wanted his agony to have a religious dimension.

(The usual story is that the chord signified the composer’s distress that he was a cuckold, but that seems unlikely.)

If the orchestra is more than sufficient, what are we to say of the ex-wunderkind Daniel Harding? Now in his 30’s, he hardly needs the vision of an old man conducting this symphony. Mr. Harding, who proved his worth last year in the Szymanowski Violin Concerto, was the protégé of Sir Simon Rattle, who frequently programs the work. And Mr. Harding himself has the cerebral background to give it a good show.

He did do a fine job here, from the delicate, almost sensitive opening to an especially comforting second theme. He also gave something I had never heard before on recordings, a second’s pause before the “scream”. Musically, that chord is integrated, but it so powerful that one needs that breath for the suffering emotion.

Perhaps the greatest challenge was Mahler’s most dangerous experiment, the mixture of tempos and meters in the scherzo. He and his orchestra were deft, clever, the piece was less joking than a Satanic cackle, but it worked. Compared to that the “Purgatory” movement was almost simple (and highly visual), while the second scherzo was pure Mahler, with a quirky waltz, a dance of death.

Mr. Harding took the finale, possibly the last outpourings of Mahler, not as an emotionally “correct” affirmation, but as a question. One cannot go from four despairing movements into the sunlight of blessing, like it’s the last minues of a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. Instead, the questions lingered, the repeat of the first theme (a Cooke innovation?) a welcome memory, and the end was suitably tender.

Tender...or perhaps the final brief transfiguration after an hour-plus of dying. Whatever the purpose, Mr. Harding’s final notes were not so much an affirmation as an inevitability.

His challenge with the New York Philharmonic was an awesome one. But without unraveling the skeins of the Tenth Symphony, he offered a puzzling troubling and memorable tapestry.

Harry Rolnick

|