|

Back

Järvi’s Turangalîla Stirs Cincinnati Cincinnati

Music Hall

03/25/2011 - & March 26, 2011

Johann Sebastian Bach: Keyboard Concerto No. 1 in D Minor, BWV 1052

Stewart Goodyear: Count Up

Olivier Messiaen: Turangalîla-Symphonie

Stewart Goodyear (piano), Cynthia Millar (ondes Martenot)

Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paavo Järvi (conductor)

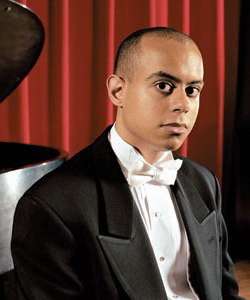

S. Goodyear (Courtesy of CSO)

Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie isn’t exactly an orchestra perennial, but it has made an appearance on Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra concerts twice in the past 10 years.

Its most recent outing took place March 25 and 26 at Music Hall in Cincinnati, almost ten years since its CSO premiere in May, 2001 led by then music director Jesús López-Cobos. On the podium this time was music director Paavo Järvi in a performance to make the timbers of the old hall shiver (that’s saying something, with its 3,516-seat capacity).

Guest artist and the hero of the evening was pianist Stewart Goodyear, who not only played the fiendishly difficult piano part in Turangalîla – almost a piano concerto in itself – but Bach’s Keyboard Concerto No. 1. Goodyear also composed the evening’s opener, Count Up, a world premiere fanfare commissioned for Järvi’s 10th (and final) anniversary as music director and the 50th anniversary of Cincinnati’s classical music radio station WGUC-FM.

Key to the title of Count Up is a numerical sequence of ten cymbal strokes repeated ten times, but no matter the analysis. It made for exhilarating listening, with its brass edged, jazzy rhythms and melodic appeal, building to an exuberant, affirmative end. After taking his bow for Count Up, Goodyear sat down and delivered a fully satisfying Bach. Performing on the orchestra’s newly acquired Steinway grand piano, he went for a close collaboration with Järvi and the CSO strings, who obliged him with a keenly expressive accompaniment. The thinnest and fullest textures were informed by the same energy and precision throughout for an exquisite, hand-in-glove effect.

Commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony, Messiaen was given no restrictions in composing Turangalîla and he seemingly imposed none on himself. It is an immense, 75-minute ode to love in all its carnal and spiritual dimensions, a far cry from his religiously inspired works, but perhaps not so far considering love as the life force, for good or ill (think Tristan and Isolde). The CSO filled the stage to overflowing with keyboards, winds, brasses, percussion and strings (68 strings in the score, here one stand fewer per section for space reasons). Music Hall, built in 1877 for such extravaganzas (choral festivals), welcomed it all.

Front and (almost) center was the ondes Martenot, a kind of early synthesizer with stops and the ability to glide between pitches, played with elegance by Cynthia Millar. In ten movements, Turangalîla was surely a feast for the senses and Järvi reveled in it, drawing herculean playing from the CSO.

Highlights (numerous) ranged from the gargantuan to the intimate. The former included the huge crescendo pile-on ending Joie du sang des étoiles (“Joy of the Blood of the Stars”). The latter included Jardin du sommeil d’amour (“Garden of Love’s Sleep”), with its muted strings, piano birdsong and woodwinds.

Others: the CSO brasses who brought Quetzalcoatl to life every time they sounded the imposing “statue theme” (Messiaen likened the theme to images of Mexican gods); the clarinets on the gentle “flower theme”; Goodyear’s knuckle-twisting cadenzas; the percussionists, seven of them, who wielded wood block, bass drum and all objets in between; Chant d’amour I (Song of Love I) with its sweet refrain and sprightly theme; Chant d’amour II from its Gershwinesque beginning to its sweeping refrains, like ink spreading in the water; Millar soaring on the ondes Martenot in Joie du sang des étoiles; Développement de l’amour (Development of Love), climax of the symphony and love-death, with its three overwhelming statements of the “love theme”; and Turangalîla III variations, with perky winds and lots of augmented fourths.

Nothing really prepared the audience for the joyous Finale, however, which, urged by Järvi, reached an unprecedented decibel level at the end and thrilled Messiaen fans throughout the hall.

Mary Ellyn Hutton

|