|

Back

Riveting, Confounding... Toronto

The Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts

02/05/2011 - & February 9, 11, 13, 19, 22, 24, 26, 2011

Johns Adams: Nixon in China

Robert Orth (Richard Nixon), Maria Kanyova (Pat Nixon), Chen-Ye Yuan (Chou En-lai), Adrian Thompson (Mao Tse-tung), Marisol Montalvo (Chiang Ch’ing), Thomas Hammons (Henry Kissinger), Lauren Segal, (Nancy T'sang), Rihab Chaieb (Second Secretary), Megan Latham (Third Secretary)

Canadian Opera Company Chorus, Sandra Horst (Chorus Master), Canadian Opera Company Orchestra, Pablo Heras-Casado (Conductor)

James Robinson (Director), Allen Moyer (Set Designer), James Schuette (Costume Designer), Seán Curran (Choregrapher), Paul Palazzo (Lighting Designer), Brian Mohr (Sound Designer), Wendell K. Harrington (Video Designer)

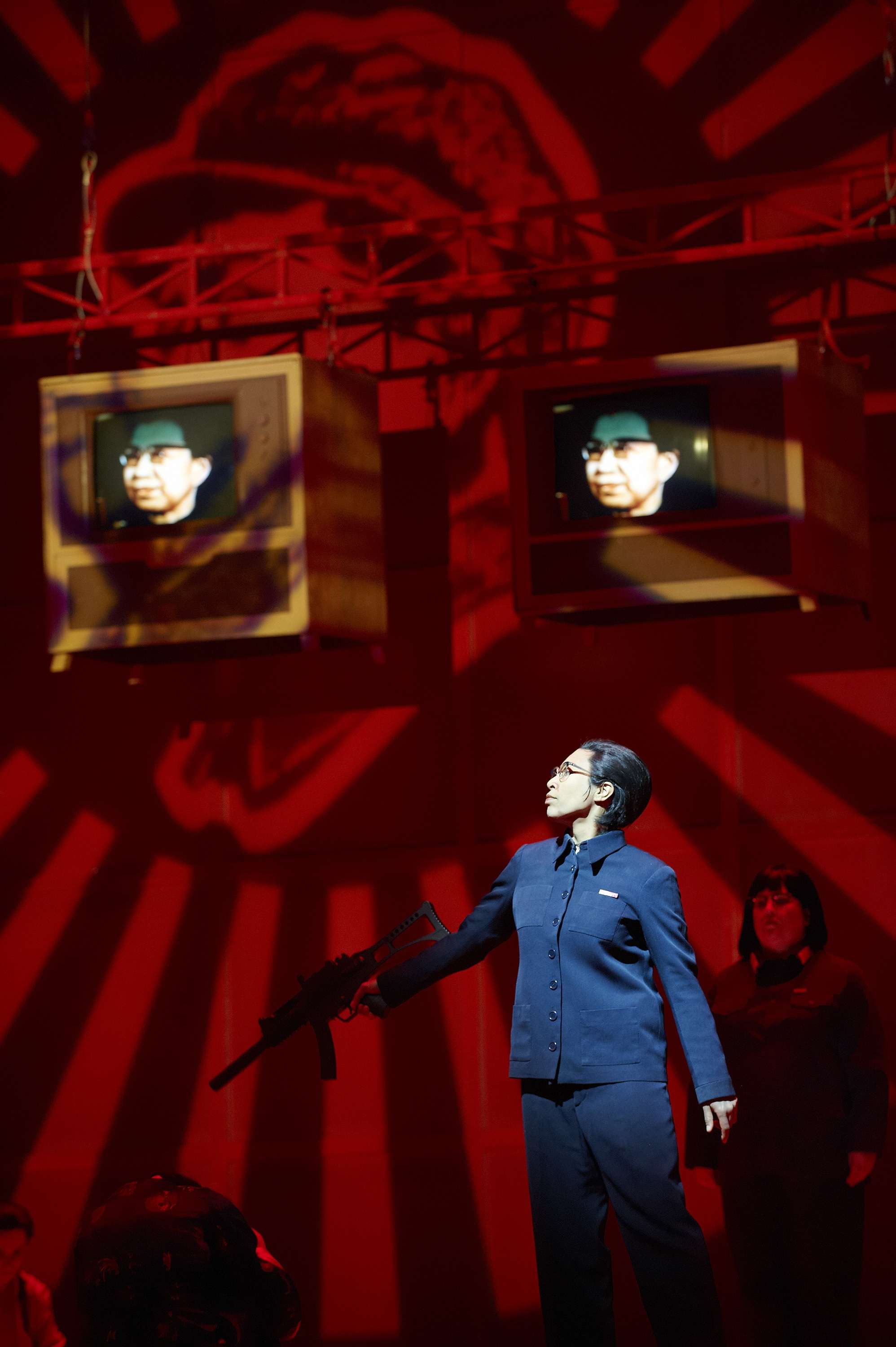

M. Montalvo (© Michael Cooper)

What Winston Churchill said of Russia - “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma” - certainly applies to Nixon in China, especially to Alice Goodman’s libretto. Frequently overheard at intermission and afterward: “I’m confused”. This hardly comes as a surprise.

Before the lights go down chorus and supers assemble on stage and commence Tai Chi movements. A Chinese peasant woman wanders about - she is a silent presence throughout the entire performance. The opening chorus proclaims “The people are the heroes now”. Accompanying a thrilling orchestral surge, a bank of 12 chunky 1970s-style video monitors descends from the flies, each showing the presidential plane’s arrival. This design motif clearly signals one of the work’s themes, namely the media saturation of this historical event. We see a typical American family watching TV while dining from their TV tables; by the end of the act they have switched to Chinese food (one of many amusing touches).

The Nixons are greeted by Chou En-lai; ordinary pleasantries are exchanged and Nixon performs an aria “News (repeated 12 times) has a kind of mystery”. Scene II takes us to the study of the doddering, frail Mao Tse-tung, who spouts a contradictory mix of observations and aphorisms. There’s a verbal sparring match that neither side wins. Scene III takes place at the diplomatic banquet during which Chou En-lai has his major aria. The act ends with everyone in a jubilant mood.

The first scene of Act II focuses on Pat Nixon as she makes a First Lady’s tour of a factory, school, hospital, farm, etc. We are amused by bouncing pigs (really!) Mrs. Nixon is presented as thoughtful, compassionate and somewhat naive.

The second scene is the turbulent high point of the opera and this is where things get very confusing. The assembled party attends a performance of The Red Detachment of Women, one of the kitschy agitprop ballets assembled by committee under the direction of Mao’s wife, Chiang Ch’ing. The dastardly villain of the piece is performed by the Henry Kissinger character who lusts after the oppressed heroine while repeating in falsetto the line “Man upon hen”. He orders her to be whipped to death; this provikes an incensed Pat Nixon to intervene in the stage action (just as in Jerome Kern’s Show Boat a Backwoodsman disrupts a lurid damsel-in-distress melodrama). Richard Nixon then intervenes, there is an extended musical quote from the finale of Die Götterdämmerung, then there is a thunderstorm (terrific lighting!), everyone gets wet (they’re outside? in February?), and the performance resumes with the heroine of the piece shooting the villain. This turns out to be the wrong thing to do and she is humiliated (and spat upon) by the other performers. This leads to Chiang Ch’ing’s big moment and she ends the act with the stratospheric “I am the wife of Mao Tse-tung.”

This scene brings back memories of the happenings I participated in back in the 1960s.

The final act is actually a coda to the work, offering a complete change of mood. At the end of a long day, both couples (the Nixons and Mao and his wife) retire to their quarters, light cigarettes, dance fox trots, and reminisce about their earlier days. Cocktail lounge music emanates from the pit while we see the “just plain folks” side to these historical heavy hitters. Chou En-lai gets to deliver the final lines with a curious benediction: “...the chill of grace/Lies heavy on the morning grass.” (The “chill of grace”?)

A libretto based solely on documented quotes runs the risk if becoming numbingly mundane, but in her efforts to avoid this Goodman goes off in whimsical directions. The music, however, has great vigour (parts remind me of what Bernard Herrmann composed for a favourite film, Hitchcock’s North by Northwest). A good deal of concentrated counting is required by orchestra members - understandably so, given the rhythmic complexities of an unfamiliar score.

John Adams’ scoring for the work calls for amplification, not to compensate for sonic miscalculations but as an intention from the start. The Mozart-sized orchestra is a lot louder than anything Wolfgang Amadeus would have devised. It includes a synthesizer (with its electronic amplification) and a fair number of brass instruments (four saxophone players, for example). Thus the need for a Sound Designer, in this instance Brian Mohr, who has worked on many projects with Adams. However there is much less amplification than in the other production of the work I attended (last March in Vancouver, reviewed on this website). The singers wear head mics (very cleverly concealed by the makeup people), and there are microphones taped to the stage front and a few within the orchestra pit. The resulting sound is not fake, perhaps because balances still aren’t always ideal, especially during the rambunctious scene in Mao’s study in which tenor Adrian Thompson manages the high-flying lines well, but there still seem to be sweet spots on the stage for him.

Genial young Spanish conductor Pablo Heras-Casado makes his North American debut here - and he returns to Toronto in the fall for Iphigénie en Tauride. We look forward to that.

Thomas Hammons, who created the role of Henry Kissinger at the world premiere in 1987, achieves the best word clarity among the cast, although Robert Orth as Nixon (a well-practiced and convincing portrayal) is terrific also. The warm-voiced Chen-Ye Yuan capably voices the work’s most reasonable character, the philosophical Chou En-lai.

Maria Kanyova, like Hammons, Orth and Yuan, has previous experience in her role. She certainly is the very picture of Pat Nixon and her attractive lyric voice comes through nicely.

Making her role debut is Marisol Montalvo as the imperious Chiang Ch’ing (whose unrepentant fury at her show trial in 1981 must have influenced the opera’s creators). Montalvo’s laser-like voice makes her a terrifically good fit for the role. Her body language, mostly stern but sometimes slinky, is also eloquent.

The fact that this production (first seen in St. Louis in 2004) is shared with six US companies has no doubt given it a generous budget supporting its high production values. Sets, lighting, choreography (along with terrific dancers), the ever-present video projections - it has it all, despite its baffling aspects. Added bonus: it sparks a lot of conversation.

Michael Johnson

|