|

Back

Definitely Outside of the Box Barcelona

Gran Teatre del Liceu

09/27/2010 - & September 30, October 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17*, and July 21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 2011

Georges Bizet: Carmen

Josep Ribot (Zuniga), Àlex Santmartí (Moralès), Roberto Alagna (Don José), Erwin Schrott (Escamillo), Marc Canturri (Dancaïre), Francisco Vas (Remendado), Abdel Aziz Mountassir (Lillas Pastia), Eliana Bayón (Frasquita), Itxaro Mentxaka (Mercédès), Béatrice Uria-Monzon (Carmen), Marina Poplavskaya (Micaëla), Xavi Estrada (Escamillo)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, José Luis Basso (chorus conductor), Marc Piollet (conductor)

Cor Vivaldi-Petits Cantors De Catalunya, Òscar Boada (chorus conductor)

Calixto Bieito (director), Alfons Flores (set designer), Xavi Clot (lighting designer), Mercè Paloma (costume designer)

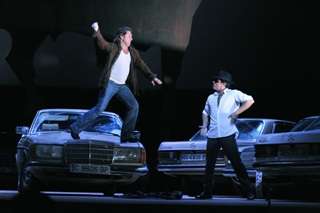

R. Alagna & E. Schrott (© Antoni Bofill)

This co-production of Gran Teatre del Liceu/Teatro Massimo (Palermo)/Teatro Regio (Torino), directed by the always controversial Calixto Bieito, was the return of Carmen to Liceu after an absence of 17 years. One is never quite sure what to expect when a Bieito show takes the stage, but either he has mellowed a bit or the houses have asked him to tone things down, for this was far tamer than his Don Giovanni of 2008. His productions feature shameless violence and gratuitous sex, often to the point where one wonders where the music has gone as it becomes buried under layers of muck, and the disgusting becomes commonplace. The Liceu Carmen , based upon a 1999 outdoor staging, did contain some simulated sex acts and a totally nude soldier, taking a turn as an imaginary matador in the moonlight danced the Act 3 prelude, but it was quite tame by the Bieito’s usual standards.

Gone are the fussy sets of Seville in 1830 as the time has been moved to the late 1970’s and the stage is circular, as an omnipresent, empty bullfighting arena, the barrier in the back containing various puertas, or doors, through which the bulls and their matadors would enter the ring. To complete the effect, the entire stage was built out over the orchestra pit, forcing the half of the violas and all of the woodwinds to sit about 3 meters under the proscenium and thereby compromising their sound, as well as the elimination of the harp, which left the flute solo in the prelude to Act 3 sounding anemic and distant. On stage additions came in the form of a large mast and a telephone booth in Act 1 and a battered Mercedes automobile in Act 2 (I still haven’t figured out the reasoning for this).The latter was joined by two more cars for the smuggler’s lair of Act 3, then a very large Osborne bull. The final scene took place on a bare stage. Excellent lighting made the most of the empty settings and the scene changes were accomplished quickly by the supernumeraries in Legionnaires costumes. The housecoats worn by the women’s chorus in Act 1 were an odd choice, but the eclectic costumes of the gypsies were a brilliant with nary a flouncy skirt or mantilla in evidence. One wishes that as much attention had been paid to the props in which there were glaring errors. Huge, flat screen TVs and stainless steel microwave ovens had not been invented in the 70’s, so wouldn’t have been smuggler’s fare, and the constantly moving limb on the golden cat which was waving away on the dashboard of a car during the entire first scene of Act 3 was horribly distracting. The finest moments were accomplished by very minimal means - the chorus became a swarming crowd and the audience into the procession of bullfighters, all by the means of the lifting of a plain rope, stretched across the front of the stage. This simple movement transformed an often garish and overdone scene into the most effective moment of staging I have ever witnessed in an opera house.

Luxury casting should have made everything perfect, but instead, the unevenness in the singers only served to highlight the errors. Béatrice Uria-Monzon was a wonderful Carmen back in the 1980s and was even credible in the very early 90s, but her voice has grown too dark and dull for the role which left her having to push and pound for emphasis, and often without enough breath to sustain a phrase. Her acting was quite good, even if her direction was puzzling at times. Bieito on one hand presents a sexually uninhibited, free-spirited woman who takes what she wants when she wants it, but then presents her as a victim in the last scene; one who is first exasperated with Don José and then terrified of him, crawling away in fear when she should be taunting him and setting the scene for her own demise. She even places the ring back on José’s finger rather than throw it to the ground to spur his rage. Thus, we are left with an impression of Carmen as a scared and helpless woman as opposed to one who has seen her fate in the cards and is prepared to face it on her own terms.

In contrast, Roberto Alagna was in excellent form, sounding better than I have heard him in the past two years, never letting up from his duet with Micaëla in Act 1 to the very last note of the evening. He paced himself very well, never overpowering his singing partners, which would have been very easy for him to do. His “Flower Song” was perfection and received the biggest ovation of the evening.

His Don José was no gentleman-gone-wrong though, as we see flashes of his rage and violent nature which run contrary to the picture of him as painted by the music. These peeks into his character made his shift to murderer not as surprising but it also constrained Mr. Alagna’s acting in the final scene, as instead of the usual thrust of the knife into Carmen’s heart, he slashes her throat, smears her blood on her face, looking as if even his emotions had been ordered by direction.

As Escamillo, Erwin Schrott created a character within a character. He parodied the “Macho Spanish male” to the point where it actually interfered with his singing of the “Toreador Song”, rolling his r’s out to where they seemed tangled in his tongue. When dressed in his unbuttoned white shirt, tight black slacks and black fedora with a jacket slung carelessly over his shoulder, he was almost cartoon-like, but oh-so-perfect for the role. By Act 3, he was in perfect voice and his duet with Mr. Alagna was mesmerizing. Not only were they well matched vocally, but the physical action, with the two men jumping onto and off of the beat up automobiles took things up to a level seldom encountered in well-choreographed fight stage-fighting.

My main reason for wanting to see this particular cast was to hear the Micaëla, Marina Poplavskaya. She has had an almost meteoric rise to international stardom over the past two years. HD broadcasts, recordings and roles in major houses all over the world seemed to make this young woman a force to be reckoned with. However, there is always a danger in casting several years in advance, leaving singers the choice of cancelling a contract or singing a role which no longer suits his/her voice and that has seldom been more evident than here. Ms. Poplavskaya’s voice is far too heavy for Micaëla; her timbre was not even throughout her passagio, forcing her to resort to portamento just to get from one note to the other with seriously weak singing in the top notes. It didn’t help that Bieito’s Micaëla is not the sweet, kind young country girl that we expect. This is no demure, shawl-wearing miss who braves the terrors of the big city to talk to intended; rather, she is a tough, calculating woman who aims to get Don José by cozying up to his mother and worming her way into his life. She was dressed in tie-dye pants and a trench coat and didn’t even seem afraid when she was about to be roughed up by the men in the gypsy gang. Sadly, her "Je dis que rien ne m'épouvante" garnered no applause, nor did it merit any.

The secondary roles also showed some problems. Itxaro Mentxaka (Mercedes) looked old and her top notes were heavy and muddled while Eliana Bayón (Frasquita) was shrill and unpleasant sounding all across her range. Their voices clashed badly when singing together and made their part of "Mêlons! Coupons!" almost painful. Àlex Sanmartí as Moralès showed promise but sounded tired by the end of the run and Josep Ribot’s Zuniga was miscast, neither vocally capable nor commanding as an actor in a role which must carry some authority.

The chorus, under the direction of José Luis Basso was the real star of this production. They sounded good across the board, and the women’s chorus in the Act 1 fight scene, which requires a series of short, tight verbal ripostes, was truly excellent. Òscar Boada taught the Children’s Chorus well, and the group, all girls, was utilized more extensively than is usual for this opera.

Marc Piollet was an enthusiastic Maestro but his tempi were uneven and on one occasion, Escamillo’s Act 3 entrance through the chorus, he seemed completely lost and the orchestra almost came to a halt.

At the close of the evening all was forgiven and the cast was afforded nine curtain calls by the always appreciative Liceu audience. Barcelona is a city that loves opera and the full house proved that. Now I can say that I’ve seen a Calixto Bieito production in person and the innovative twists of staging, along with the excellence of the two male leads made it a very enjoyable experience.

Suzanne Torrey

|