|

Back

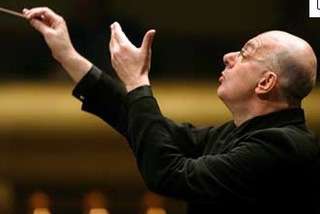

Leon Botstein Introduces Schmidt with Force and Glory New York

Annandale-on-Hudson, Fisher Center Bard College

08/21/2010 -

Alban Berg: Der Wein

Franz Schmidt: Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln

Christiane Libor (soprano), Fredrika Brillembourg (mezzo-soprano), Thomas Cooley (tenor), James Taylor (tenor), Robert Pomakov (bass-baritone)

Bard Festival Choral, James Bagwell (choral director), Ken Tritle (organ), American Symphony Orchestra, Leon Botstein (conductor)

L. Botstein (© Steven J. Sherman)

The lush voice of Christiane Libor filled one of Frank Gehry’s very special venues for music, the Fisher Center for Performing Arts at Bard College. Libor, a European soprano on the cusp of a big career, was singing Der Wein, an aria with orchestra by Alban Berg. Berg’s setting of three Baudelaire poems describing the joys and perils of wine was prompted by a lucrative commission from the soprano Ruzena Herzlinger, who is said to have had more money than talent. Berg halted composing Lulu at 300 bars and undertook this piece. While the piece has had steadfastly poor reviews over the years, its melodies are lovely, even those describing sleazy scenes.

Der Wein has also been trashed along the way as an ossia, a brief copy of, in this case, the French Baudelaire translated by Stefan George into German. The anagram for ossia is sosia, which means a double, or clone. Word play noun to anagram by critics of Der Wein reflects Berg’s play with the constraints of serial music and an effort to keep it modern, but still evoke the tonescape of the late romantics. Berg composed with two characteristic patterns of tonal music, the ascending minor scale and extracted alternate notes in the twelve-tone scale to create three-note chromatic figures.

Listening to Libor sing, you would never guess the piece was composed with a soprano’s limitations in mind. Libor’s top is effortlessly delivered and she dives across octaves with an ease and evenness that is remarkable. Hers is a voice of many colors, but all are woven together into a seamless tone of wide-ranging dynamics and beauty.

Botstein commanded the American Symphony Orchestra with precision and also latitude on the lyrical lines, as Libor sang with a comfortable power. Der Wein was intoxicating.

Berg and Franz Schmidt were placed on this program together not only because the two pieces were composed at about the same time, but because both composers grapple with making modern music and keeping some of the lyricism and beauty of the romantic period. Schmidt is the more conservative, often harking back to the Baroque with his references.

Schmidt is not a household name, and, in fact, largely disappeared after the Second World War because, although he died in 1939, his music was later used by the Nazis to rally the Aryan forces. The piece had the misfortune to premier just after the Anschluss, in March, 1938. Botstein bravely makes the case for the importance of Schmidt’s music in the program notes. Without “whitewashing the past,” Botstein notes, “we can again appreciate the inspiration, power and relevance” of Das Buch mit sieben Siegeln, “one of the greatest choral works of the 20th century.” Detached from politics, it is a thing of beauty if not a joy forever.

The stage was filled almost to the rafters, with chorus stage front, the sopranos and altos in a wedge at down stage right and the tenors and basses stage left. The soloists were at the center, with a narrator/tenor, the magnificent Thomas Cooley, to the left of the conductor. Performing with a sturdy, clear voice, Cooley approached "Sprechgesang" from time to time as he narrated from The Book of Revelation. After Cooley sang an introductory devotional, he yielded to the bass-baritone Robert Pomakov as God. When this authoritative and rich voice sings that he is the “Alpha” and the “Omega”, you buy in.

The Bard Festival Chorus under James Bagwell kept the proceedings contained, but with great feeling and drama. To cite only a few moments of extraordinary passion: a chorus of warriors extol death and plunder, and demand that children be torn from their mother’s love as the mother’s chorus cries out in torment. A violently agitated chorus, cut through by angular trumpet figures, sings in horror as stars fall to earth, the sea overflows and the sun goes black.

The Book of Revelation on which this oratorio is based, was called to attention in Ingmar Bergman’s groundbreaking Seventh Seal, so we are prepared for the agony as the seals are opened and a Jobian demand made for humans to accept what is delivered and go forward. How do you hold on to difficult beliefs in periods of great tumult? It is tempting to think of this as a meditation on jihad, but the entire work is firmly based in Catholic tradition and Christianity, no satanic work.

Christiane Libor sang in Das Buch with great beauty. Fredrika Brillembourg’s rich mezzo and tenor James Taylor, the go-to singer for Bach’s Evangelist, both sang arresting solos and also joined the ensemble. The dynamic Robert Pomakov, in quartet singing, and also as God in solos, provided a masterful bass-baritone of wide and even range.

Kent Tritle performed an organ solo with vigor. This is no tame piece and not a performer on stage failed to rise to the challenge.

While Schmidt criticized Mahler in words, his music is in color and scope a homage to him, as it is to Schoenberg and J.S. Bach. The “Hallelujah” rivals Handel’s, although it is often cited as an example of the influence Hungarian gypsy music on Schmidt and called an “ungarischen” Hallelujah. The male chorus follows singing a subdued Thanksgiving on three notes in the manner of a plainchant. These passages barely scratch the surface of the musical references Schmidt used in his apocalyptic oratorio.

The music evoked by Botstein and the orchestra was wrenching and eloquent. The texture of the piece was fresh and transparent even in the quadruple fugues Schmidt handily created (Der Appell zum Jungsten Gericht). Botstein gave climaxes space to expand, and the front to back perspective was deep. This is not a desk-bound view of the Apocalypse in which the composer’s imagination fails to take wing.

This rewarding score in which feeling elevates cannot be dismissed. Botstein champions Schmidt’s place in the musical pantheon by bringing such a thrilling production to Bard.

The finale brought down the house. Into a venue where people of all hues and beliefs gather, this glorious oratorio left behind its reputation as only an Austrian classic, one that does not travel. In Botstein’s hands Das Buch has traveled with nobility.

Bard Music Festival

Susan Hall

|