|

Back

Not a particularly promising debut Zurich

Tonhalle

05/29/2010 - & May 30th, 2010

Gustav Mahler: Adagio from Symphony No. 10

Dmitri Shostakovich: Cello Concerto No. 1 op. 107

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 op. 92

Alban Gerhardt (cello)

Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, David Afkham (conductor)

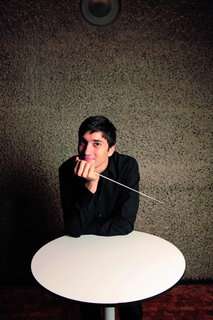

D. Afkham (© Ben Wright)

It is Whit-Monday and, as Managing Director of the Tonhalle Orchestra, you hear from Andris Nelsons to say he cannot now conduct two concerts the following weekend due to indisposition. A hundred telephone calls later (allegedly, including to Bernard Haitink and Herbert Blomstedt, both residents of nearby Lucerne) and a replacement conductor is found: a 26-year-old German by the name of David Afkham, a former assistant to Haitink, who has conducted the London Symphony Orchestra. Nelsons was to have conducted Richard Strauss’ Don Quixote and Beethoven’s Eroica but Afkham fears he does not know either work well enough. Instead orchestra and soloist agree to change the programme fundamentally.

It was evident from the outset of the Mahler that Afkham’s conducting technique was standard but rather dull, at least without histrionics. The piece does not make an ideal overture (where have all the traditional overtures gone?) but although Afkham highlighted and contrasted the hushed resigned passages with the anguished outburst towards the end of the movement, he brought little insight into the piece. The work followed the composer’s marital crisis with Alma and was written just a year before he died, never to complete the work.

Alban Gerhardt then launched straight into the technical vigour of the Shostakovich clearly more than comfortable with the work’s complexities, such as the eerie harmonics in the slow movement. Perhaps the sorrowful Cadenza seemed overlong due to a lack of accentuation but there was no shortage of pyrotechnics when required and the Allegro con moto was driven forward forcefully by soloist and conductor to bring the work to its thrilling conclusion. Enthusiastic applause brought its just reward, Gerhardt making his instrument sing with some J.S. Bach. The audience’s sigh of pleasure at the end was audible.

The second half of this concert tested the young conductor. When a youngster steps in, at short notice, to replace a Big Name, he must naturally do so with a degree of trepidation. One orchestra member told me that Afkham had started rehearsals in far too serious a vein but soon relaxed when the orchestra showed themselves as friends rather than ogres. To an extent, this was also reflected in performance. At first, in the opening Vivace, Afkham was far too tense, only relaxing as the work progressed and smiling by the last movement, when the end was in sight. Of course the power and vigour of the work should suit a young conductor, given its strong rhythmic potential, the “apotheosis of dance” to quote Wagner. Afkham whilst maintaining steady tempi throughout, and displaying youthful verve, accorded the work little individuality. The Allegretto was perhaps the least successful movement, even though the Principals of the orchestra served him well. The fast passages in the Presto were all clearly articulated, followed by the helter-skelter rush of the Allegro con brio played with visible enjoyment by all sections of the orchestra.

The orchestra knew this work well, hardly needed a conductor, having recorded it to general acclaim under their Chief Conductor David Zinman and through regular outings. The young conductor was unable to introduce many insights into the work and one was left with a certain sense of emptiness.

How many concertgoers, however, were alert enough to spot the first-half’s soloist, not in standard orchestra uniform, supporting the cellos in the Beethoven from the back desk?

John Rhodes

|