|

Back

A Mighty Fortress Was His Music New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

10/24/2008 -

Leonard Bernstein: Mass: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players and Dancers

Jubilant Sykes (Celebrant), Asher Edward Wulfman (Boy Soprano), Ryan Kiernan (Acolyte)

Street Chorus, Morgan State University Choir, Eric Conway (Director), The Brooklyn Youth Chorus, Dianne Berkun (Founder and Artistic Director), Stony Brook University Marching Band, John J. Leddy (Director), Leslie Stifelman (Music Supervisor), Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop (Music Director and Conductor)

Sean Curran (Musical Staging), Alan Adelman (Lighting Designer), Acme Sound Partners (Sound Design), Jessica Johan (Costume Consultant)

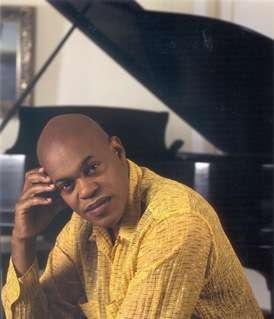

J. Sykes (© Terrence McCarthy)

Ever since God ran away from us human monsters, composers have been free to use whatever words they wanted for the original Catholic Mass. Brahms, Delius, Britten and countless others used poems both sacred and secular, with great success. So when Leonard Bernstein, who had composed several works on Old Testament themes, was commissioned 36 years ago to write a work for the inauguration of the Kennedy Centre, one would never have expected him to use Catholic religious dogma for his vehicle.

Bernstein, though, surprised the multitudes (though probably not the adventurous Roman Catholic Jacqueline Kennedy) with a Mass that, did not entirely depart from the original Catholic Mass, that employed Latin, yet was transformed - literally - into an iconoclastic setting.

It was, and is, almost impossible to stage, since it uses dancers, several choruses, a few boy sopranos, actors, a huge orchestra, marching band, three saxophones, two guitar players and, yes, a banjo. Nor is the two-hour performance everybody’s cup of sacramental wine. These past two months, when Bernstein has been played over and over again, even his greatest devotees are beginning to hear the same semi-jazz, the same canons, the same percussive “street-smart” choruses, and almost always, the same closing choruses which—no matter what has preceded it—has yearning and pathos and glory and unashamed Late Romantic harmonies to make its emotional point.

This is not to denigrate Leonard Bernstein’s genius as a composer (as well as pianist, conductor, spokesman, and everything else that it’s possible for a human being to do in a single lifetime). But sometimes, as this rabbi’s grandson might have said, “Enough is enough already.”

Nonetheless, the Mass, when performed right, has the Bernstein power, and the Bernstein enigmas. And the production by the ever more amazing Marin Alsop, who had studied with Bernstein, was an excellent one. The Isaac Stern Auditorium had no extra staging, but the battery of lights turned the walls and sides different colors, from churchly stained glass to demonic red. The audio system was rigged so, when necessary, sounds came from around the whole auditorium. The stage managed to fit orchestra, choruses, and soloists, but also housed a Sacramental Table from which the icons could be smashed (yes, the literal iconoclasms), Ms. Alsop stood on what could have been a church podium, and the various choruses entered and exited throughout the show, and the Celebrant—the Priest of the occasion—donned various robes to show his feelings about the service itself.

That Celebrant was the noted singer Jubilant Sykes, who could have carried the whole show without benefit of orchestra or choruses. Not only was his baritone rich and clear, but he could effect the softest pianissimos, the loudest cries for help, agonizing interplays with the cynical Street Chorus (actually 20 actor-singers from Broadway musicals), and a final departure before entering with the touching last words.

Mr. Sykes had the multitude of styles, the voice, and the acting, and I cannot possibly imagine anyone as good for the part.

Yet, this was Ms. Alsop’s production, and she led her Baltimore ensemble with all the symphonic syncretism which Bernstein had demanded. The two Meditations were for orchestra alone, and the transparency of the Beethoven quotes and the touching sounds of the first “peaceful” meditation were noteworthy. Nor did she stint in the so-called jazzier portions. The Gospel sermon God Said, the Mad Scene of Things Get Broken and the rock/blues chorus of Don’t Know came forth with all the energy needed.

Granted, half of these choruses sounded exactly like the Officer Frumke song from West Side Story, for this was a Bernstein show (a show without Sondheim lyrics), but that was Bernstein’s choice. Also, the choral words were often swallowed before getting out to the audience, so the religious controversies engendered weren’t as transparent as they should have been.

As for the typical Bernstein finale—this time endless canons sung over and over again in different keys—well, musicians probably can see through the little tricks to make it work. But it did work.

Not for everybody, alas. Nearly a dozen people walked out during the Mass, though whether for religious, musical or urinary reasons was difficult to determine. It doesn’t matter. Ms. Alsop took one of the most arduous ensemble pieces ever written, and gave it all the bumps, grinds, pulsing and dancing required, from the opening offstage Kyrie to the young people holding candles walking down the aisles.

And to those who still ask whether this jazzy, bluesy, rhythmic, show-biz work is religious, one can only say that for Leonard Bernstein, religion was music itself, and a far mightier fortress than any hirsute old Gospel divinity.

Harry Rolnick

|