|

Back

The Voluptuary and the Aphorist New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

05/04/2023 -

Karol Szymanowski: Songs of the Infatuated Muezzin, Op. 42

Győrgy Kurtág: ...concertante..., Op. 42

Boris Tishchenko: Symphony No. 5, Op. 67

Sun-Ly Pierce (Mezzo-soprano), Luosha Fang (Violin), Rosemary Nellis (Viola)

The Orchestra Now (TōN), Leon Botstein (Founder, conductor)

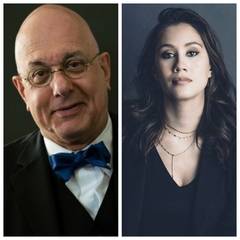

L. Botstein/S.-Y. Pierce (© Matt Dine/Courtesy of the artist)

“I never hear my ideas properly... No one can hear it... There’s nothing to be done... I felt I couldn’t go on, I mustn’t go on...”

Győrgy Kurtág

“Every idea he writes is essential. There is never any idea of small talk. There is never the idea of wanting to please an audience. Every phrase has tension, detention, and not single abstract note or abstract interval. For him, there is only the sense of truth.”

Heinz Holliger on the music of Győrgy Kurtág

Leon Botstein’s title for the three works played by his The Orchestra Now (TōN) was misleading. “Before & After Soviet Communism” assumed politics. But Karol Szymanowski was too aristocratic for politics. Győrgy Kurtág is too ethereal for politics, spending most of his life in his native Hungary. While Boris Tishchenko was quite successful under Stalin. (Though his true feelings came out after Stalin’s death.)

Rather, this writer would call the program title “Sensual, Spectral and....er...Shostakovich‑ish.” (Shostakovich‑ian??)

At any rate TōN, under Mr. Botstein, offered some astonishing music, no matter how you listened. Even more astonishing, since Mr. Botstein’s eight‑year‑old TōN started as an international graduate program at Bard, and has now been elevated to the front ranks of experimental programming.

The program was hardly easy for any audience–and, as expected, Carnegie Hall was hardly filled up for the occasion. The Tishchenko Symphony was new, of course, though its conscious homage and style to his teacher-friend Dmitri Shostakovich was well appreciated. Just the opposite, Győrgy Kurtág’s rare long orchestral work, ...concertante..., demanded–and rewarded–the utmost concentration.

The opening needed no excuses. Szymanowski, born in Ukraine but decidedly Polish, wrote music of near‑carnal lubriciousness, well suiting his own life. Happily rich, happily homosexual, joyously traveling through the Middle East, he wrote Songs of the Infatuated Muezzin with obvious elation, depicting the anguished Islamic cantor longing after a woman. The original poems by Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz were sensual enough for any woman to soar to the highest reaches, for the orchestra to seek sweet Arabic melliferousness or low‑down acidity.

One was astonished to read that Sun‑Ly Pierce was billed as a mezzo-soprano. From the start, this music had a soprano range, soaring just on the juncture of high C, and rarely leaving it. Whatever the range, Ms. Pierce was dramatically the right voice for the oh‑so‑voluptuous poetry.

I see the program notes compared this piece with the “clichéd Ravel Sheherazade”. That’s a needless insult. Neither work simulates real Islamic music, but both composers clothed their own notes with a stylized replica. And both are stirring.

R. Nellis/L. Fang

Mr. Botstein gave a requisite introduction to Kurtág’s ...concertante..., for this demands–no, clamors for concentration. I am a devotee of Kurtág’s miniature works for voice, chamber ensemble and piano. But ...concertante... was the first time I’d heard him with a massed orchestra.

This was intriguing, since Kurtág rivals Samuel Beckett in his aphoristic epigrams. Reading Beckett means consciousness of every word. Ditto for Győrgy Kurtág.

The orchestral forces never overcame the delicate, multi-colored tones of the two soloists. Violinist Luosha Fang and violist Rosemary Nellis seemed to understand that the cryptic measures, the seemingly detached motifs needed two players of utmost sensitivity. Yes, the TōN gave a kaleidoscope of colors, patterns of consorts and solos (and even a steel drum solo). But it took the string duo to bring a contrasting transcendence to Kurtág’s quicksilver orchestral accompaniment.

And while the work was difficult at first hearing, the audience was justifiedly entranced with the soloists.

The second half of the evening was devoted to the Fifth Symphony of Boris Tishchenko, one of the “Leningrad School”, schooled by Shostakovich, surviving under Stalin–and blossoming in the last years of his life. (He died in 2010.)

I say “symphony”, but this could have been Concerto for Orchestra. Starting with a seven‑minute cor anglais solo, beautifully played by Jasper Igusa. Then, during its 45 minutes, the work had long solos by flute, horn, trombone, trumpet and clarinet, as well as strangely chordal work by the strings. (And of course the booming percussion section.)

The work quotes from Shostakovich frequently, since these movements were musical obsequies. Some were recognizable, some were obscured. Tishchenko’s connected five interrelated movements had a lot of bright spots, like the solo passages. The “sonata” section had the mordant sarcasm of Shostakovich and the finale was both balletic, percussive, and surprisingly calm, almost solemn at the finale.

It was the opposite of Kurtág’s work. Where every note in that work had its own universe, this Symphony was fat (never gross), and one’s mind could wander without guilt.

Mr. Botstein let his TōN with his usual dedication to his youthful players and of course never let the excesses of the Symphony become really tiring.

Harry Rolnick

|