|

Back

Schumann’s Pictures at an Exhibition New York

St. Bartholomew’s Church

03/22/2022 -

Robert Schumann: Intermezzi, Opus 4 – Faschingsschwank aus Wien, Opus 26 – Papillons, Opus 2 – Carnaval, Opus 9

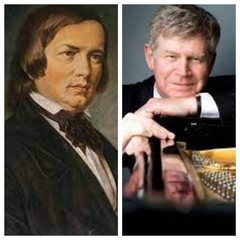

Ian Hobson (Pianist)

R. Schumann/I. Hobson

“When you play, never mind who listens to you.”

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

“To compose is to remember music that has never been written.”

Robert Schumann

Ian Hobson displayed ten incontestable reasons to hear his all‑Schumann recital last night in St. Bartholomew’s Church. Those fingers whizzed through the virtuosic sections of the composer–about 80 percent of the music. Most of the audience was mesmerized by the clarity of the densest counterpoint, the ten digits whirling over the keys, the climaxes taken with blistering velocity.

Then again, Mr. Hobson had inadvertently been waiting for this concert for the last two Plague Years. His first all‑Schumann recital had taken place prior to Covid, over two years ago, and he had prepared for two more. Not to play the complete Schumann piano music. (That would take eight or nine recitals, at least.) But to give a sampling of the familiar and the rare of the composer’s voluminous work.

The astonishment was that Robert Schumann’s piano playing had been predicted to make Liszt’s playing look like Liberace. Until, with his usual passion–a passion which later sent him to the loony bin and suicide–he attempted in 1830 to widen his digital range and paralyzed his hands. Which made it even more astonishing, that his brain alone (with the help of his virtuoso wife) could create such fiendish masterpieces.

Ian Hobson’s program included the popular Carnival, the almost-as-popular Jest in Vienna, the waltzes of Papillons and a very rare work, Four Intermezzi.

The artist was all business. No intermission, a few succinct introductions, and–thank heaven–no encores. And when he sat down to play those fearfully tough Intermezzi, the title seemed inappropriate. These were serious etudes, enough to tax any pianist. The always splendid program note of Paul Griffith detailed the differences, but I read them afterwards. Mr. Hobson’s own fingers jumped (not danced) from one Presto section to another. Mr. Hobson let his fingers do the hard work, while his mind seemed somewhere else. The best demonstration was the second, a “Presto a capriccio”, and his fingers launched into a wild almost manic exercise.

It was sheerly amazing, as were his other pieces. And yet (how can I say this without sounding philistine?) his stamina and muscularity far exceeded Schumann’s pregnant pauses, his grace.

The following Vienna Carnival was manic for much, so one was pleased with the sentimental Romanze. Carnivals are supposed to be fun, Mr. Hobson, his fingers flying over the keys, made it frenzied. Had this Schumann appeared amidst other composers, one would have enjoyed the mania. Together with the other works (the whole program was titled “Carnival Jests”), Mr. Hobson brilliance seemed forced.

Following was the Butterflies. Rather than our iridescent friends, the twelve sections had literary meanings. Schumann was an eclectic reader and writer. But one didn’t need to know the underlying meanings for the waltzes.

Carnaval is certainly familiar here and for good reason. This was Schumann’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Such variety, such diversity, such a salmagundi of technical problems has rarely be composed. The one factor missing, I felt, was the joy. Mr. Hobson had no problems with the rapid thumb figurations for (a more literal) “Butterflies”, The finger staccatos of “Pantalon et Colombine” were staggering, the left‑hand skips of “Paganini” were faultless.

Yet, oh how I missed the grace of “Chopin” or the balletic limpidity of the “Waltz Noble”. One has so much admiration for Ian Hobson’s digits, his unending stamina, the power of the finale. Still, one felt a lack of awe for the feeling and passions of this most passionate composer.

Harry Rolnick

|