|

Back

World-Sounds New York

Merkin Concert Hall, Kaufman Music Center

06/05/2019 -

“Global American Chamber Music:”

Chou Wen-chung: Ode to Eternal Pine

Reinaldo Moya, Crónica de una Muerte Anunciada

Chinary Ung: Child Song

Pablo Ortiz: Vida Furtiva

Noel Da Costa: Blue-Tune Verses

Gabriela Lena Frank: Cuatro Bosquejos Pre-Incaicos

Da Capo Chamber Players: Curtis Macomber (Violin), Chris Gross (Cello), Patricia Spencer (Flute, piccolo, alto flute), Steven Beck (Piano); Guest Artists: Nuno Antunes (Clarinet, bass clarinet etc), Michael Lipsey (Percussion)

Da Capo Chamber Players (© Jill LeVine)

Living up to their name last night, the Da Capo Chamber Players took six pieces, most written a few decades ago–and like the “da capo” repeats of Baroque music–repeated them for our enlightenment, our elucidation, and for our joy.

This isn’t to say that the audience at Merkin Concert Hall hadn’t necessarily heard the works from Cambodia, Korea, ancient Peru and Brazil before. But the Da Capo Chamber Players–with over 150 pieces written specifically for their talents–have a habit of waking audiences to an eclectic assortment which can awe or amaze or, yes, bore listeners.

What else would you expect with such multifarious origins? The four Da Capo players and their two “guest artists” could replicate sounds when they wished (the Cambodian equivalent of gamelan or Korean classical ensemble) or, with their soloists give original pictures of antediluvian Peru, or simply perform damned good music without a particular geography.

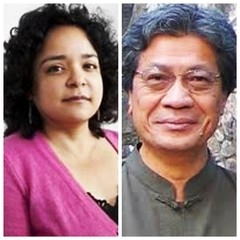

G. L. Frank/C. Ung

The beginning, Child Song was written 35 years ago by the Cambodian composer Chinary Ung, with four instruments offering his own original take on the “roneat ek” (which I knew in Thailand as the ranad ek, the xylophone/marimba ensemble). The first piano notes from Steven Beck were not only pentatonic, but he emphasized the percussive quality, introducing his own version of a Khmer ensemble.

Flute, violin and cello offered treble fantasias, varied counterpoint, all in that five-note tradition, but extending it out to include the simply eponymous child song.

This longtime resident in the area noted a double irony. First, that the Cambodian orchestra, almost eradicated during the Khmer Rouge decade, though now is revived. Second was the splendid cello solo by Chris Gross. Supposedly un-Cambodian-like, it echoes the Thai cello-like saw sam sai, itself forgotten until it was happily revived some 40 years ago.

The other “Asian” piece was by the esteemed 96-year-old Chou Wen-chung, who, as always, gleefully attended the concert. Ode to Eternal Pine was not a stylized Korean work, but seemed totally Korean, albeit with Western instruments. Percussionist Michael Lipsey provided the gongs, the others playing the equivalent of this highly sophisticated ensemble. (More than Japanese cryptic arcana, or Javanese rhythms, Korean classical music has the most intricate cerebral impact of any Eastern music.) It was a virtual tour de force for Chou Wen-chung to “translate” the music. Though somehow, the magic was lost outside of a temple or courtyard.

Before this, Patricia Spencer, the iconic flutist of modern music, took on the Nigerian/Jamaican Noel da Costa’s solo Blue-Time Verses. My admiration was less for the solo music (which I didn’t get) as Ms. Spencer’s astonishing volume control–forte without being flashy–of her instrument.

The second half, I confessed, was a relief for this listener. Asian music is fine up to a point. But when violin, clarinet and piano came together in Pablo Ortiz’ exuberant Vida Furtiva, I was granted a reprieve.

Mr. Ortiz needed no translation. Instead we had a joyous almost comic conversation between instruments. Lots and lots of trilling and dialogue, unrelenting delights among the three virtuosi. One didn’t need any explanation. Just wonderful.

Gabriela Lena Frank is the Western Hemisphere equivalent of Sofia Gubaidulina, she whose Tatar-Russian heritage embraces music of the Orthodox Church, Judaism, Bach etc etc.

Ms. Frank is “merely” of Jewish/Peruvian/Lithuanian descent, yet her music equally embraces the whole world. In Four Pre-Inca Sketches, she went further back than her own history with four all-too-short bagatelles.

Nine days ago, I had visited Costa Rica’s finest museum, that of Pre-Columbian art, and her four pieces flute and cello reflected much of the same imagery. True, instead of panpipe, Costa Rica had a simple ocarina, but the idea was the same.

Mochica flutists (© Virtual Museum of Canada)

Nothing was made to imitate the Mochica flutes or Nazka panpipes, but the trenchant, jewel-like, off-kilter quartet of works was all too short for such inspiration.

The final work was a curiosity: a ten-minute abridgement of a novel by the late Gabriel Garcia Marques. Rather than attempting to hear a Richard Strauss tone poem, I merely listened to the tones–and the virtuosic marimba/snare/bass drum playing by Michael Lipsey.

All was joyous, even the moody wedding march and the death. All the Da Capo players and guests performed Reinaldo Moya’s story with zest, dark emotions and a whizz-bang percussion ending.

Harry Rolnick

|