|

Back

Willing! Able!! And Very Very Igor!! New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium Carnegie Hall

10/04/2018 - & September 28, 29, 30 (San Francisco), October 5 (Greenvale), 2018

Igor Stravinsky: Pétrouchka – Violin Concerto – Le Sacre du printemps

Leonidas Kavakos (Violin)

San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas (Music Director/Conductor)

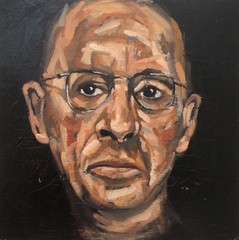

I. Stravinsky: Portrait by Christopher Wright

“I live neither in the past nor in the future. I am in the present. I cannot know what tomorrow will bring forth. I can know only what the truth is for me today. That is what I am called upon to serve, and I serve it in all lucidity.”

Igor Stravinsky, Autobiography

In the first of his “Perspective” offerings here with his beloved San Francisco Orchestra, Mr. Thomas gave us three works by Igor Stravinsky. And–no insult intended–Mr. Thomas has an unfair advantage. Other conductors study scores, rehearse, interpret and studiously catalogue the Stravinsky repertoire. Mr. Thomas, as a child, broke breakfast bagels with Stravinsky.

Just about everybody in the Los Angeles artistic world knew the Tomashevsky family, renowned artists from the Russian Yiddish theater. So when little Michael Tilson Thomashefsky showed his own wunderkind genius, his musical friends from the breakfast table were happy to help the kid along. By his early teens he already had a reputation as soloist, accompanist, and soon conductor and composer.

Hearing Stravinsky rehearse his own music obviously has paid off in triplicate. First, his personal friendship with the great artists of the West Coast. Second, his own ancestral (or genetic?) “Russian-ness”. Third his leadership of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, whose sounds were molded by Sergei Koussevitsky, also an heir of a Russian-Jewish background

The two bookend pieces of Stravinsky last night are amongst his most popular. Under Mr. Thomas’ baton, they became revivified. The conductor chose to played the second version of Pétrouchka, with the insanely difficult piano sections, played with aplomb by Mark Shapiro. (Since the composer had initially conceived this for piano and orchestra, it made sense.)

More essential, Mr. Thomas conducted the whole ballet with colorful grandeur, with a few somber exceptions in the “Moor’s Cave”. His San Francisco Orchestra has solo artists who can bring the Carnegie Hall rafters down. Note the fast blazoning trumpet solo by Mark Inouye for the “Ballerina Dance”. And with Mr. Thomas’s sense of balance, one seemed to hear every single strand of music, both from the opening “Shrovetide Fair” to the final near cacophony in the final sad movement.

It was yes, so Russian, but it was also a tapestry of Spanish dances, folk songs, orchestral crowds, and of course, through the blazing genius, the scenario of the poor puppet with the last sneering laugh. In a way, these “tunes” are always simple and attractive. Under Mr. Thomas, their simplicity was an illusion for colors for which Caravaggio would have sold his birthright.

Just as Stravinsky had scorn for Beethoven’s later music, preferring the “classical” composer, some of us prefer the theatrical un-classical Stravinsky of Pétrouchka and Sacre. Yet the Violin Concerto is one of those “middle-period” Stravinsky opuses which defies his timeline. It is jaunty, engaging, it is like a cerebral joke without a punch line, just an atmospheric delight.

Had Mozart written such a concerto, scholars would be plumbing the composer’s letters to his father, asking what events in his life would have prompted such piquant tones. Stravinsky simply composed it for a splendid fiddler.

M.T. Thomas/L. Kavakos (© Spencer Lowell/Marco Borggreve)

Leonidas Kavakos, a frequent and always welcomed artist in New York, seems to always have that jaunty spirit. In the most doleful music, his stance, his tones, his attitudes seem to say, “Hey, I’m having fun up here. Hope you can join me.”

Thus, the Stravinsky Violin Concerto was the tastiest Russian caviar. He was never less than dignified, but he knew how to change emotions in the opening, to edge near the sentimental in the first Aria but then step back, to show that it was a pretty tune, not a melancholia.

In the final Capriccio, Mr. Kavakos, eschewing even a hint of pyrotechnics, simply expanded the inspiration, letting the notes–and Mr. Thomas’ discreet conducting–speak for itself.

He had four curtain calls before the encore. While I usually look with disdain at encores after heavy lofty concertos, this work was an exception. Nobody in the audience recognized this high-stepping music, except that it was enjoyable. And a bit of sleuthing later showed that it came from Mr. Kavakos’s compatriot, Nikos Skalkottas, the second movement of his Solo Violin Sonata.

In one of those unfortunate coincidences, we heard The Rite of Spring just two weeks ago by the New York Philharmonic. Conductor Jaap van Zweden, in his official premiere, played the work with sanitized perfection. His orchestra was an ensemble of lapidary beauty, its changes of rhythms were of clockwork perfection.

The San Francisco Orchestra has first chair players of equal deftness. Trumpet, bassoon, percussion, all the winds were spot on, the string chorales were appropriately harsh, the horns didn’t have a single error.

But oh, what a difference. Mr. Thomas played an almost frightening Rite of Spring. The opening solo was held down with eerie portent. The repeated B flats in the Dance of the Adolescents were plodding, urgent. The Dance of the Rivals made Bernstein’s West Side Story fight seem like Brahms’ Lullaby.

Yet one cannot take the individual sections here. Mr. van Zweden offered a gift for the Phil’s benefactors. Mr. Thomas told the patrons to back off. He gave sudden changes as jagged as a knife. Stravinsky’s ancient sacrifices were bloodthirsty, the dances were sexual celebrations.

Again, Mr. Thomas danced through the ballet. He gave his wisdom, like Rabbi Hillel, standing on one leg. He summoned up the dances with jumps and twists. Not, apparently, done for visual effect. He simply wanted to make his flagship orchestra–an orchestra which he will continue to lead even after retiring at Musical Director this year–a group which does not rest on comfortable perfection, but on the most electrifying illusion of total spontaneity.

Harry Rolnick

|