|

Back

Adventures of a Vertiginous Virtuoso New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

03/08/2018 - & March 1 (La Jolla), 4 (Schenectady), 2018

Nikolai Obukhov: Création de l’or – Révélation (Le Glas d’au-delà)

Franz Liszt: Nuages gris, S. 199 – Années de pèlerinage (Troisième année): “Les Jeux d’eau à la Villa d’Este”, S. 163 No. 4

Olivier Messiaen: Catalogue d’oiseaux: “Le Courlis cendré”

Alexander Scriabin: Piano Sonata No. 5 in F sharp Major, Opus 53

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-Flat Major “Hammerklavier”, Opus 106

Pierre-Laurent Aimard (Pianist)

P.-L. Aimard (© Marco Borggreve/DG)

“Aimard must have broken the world’s record for number of notes in a single piece.”

Major concert-artist representative, during intermission of recital by Pierre-Laurent Aimard

Pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard played two works in his Carnegie Hall recital last night. The second half sonata was a celebration of the piano, of inspiration and the deepest depths of human emotion. This was the 29th Sonata written by Ludwig van Beethoven.

The first half was a celebration of (“Take a deep breath”) birth and truth, Satanic distress, birds on bleak marshes, fireworks, death knells, fountains, misty clouds, resplendent fountains and ecstatic emotions.

And this single “movement”–played without a single break–was written by one Catholic-naturalist disciplined mystic, two half-crazy Russian spiritualists and one Hungarian tone-painter, encompassing almost a whole century.

That first half of the recital did show Pierre-Laurent Aimard as a pianist of dizzying brilliance. Though such unending dizziness from four different composer became a giddy mixture of tone-clusters, bird-songs, insanely difficult double octaves, and non-pausing, non-stop performances on the utter extremes of the keyboard.

So giddy, so extreme, so volatile, that breathless notes became, alas, breadthless notes. Yes, one could catch the grace and phrasing of Liszt’s Fountains of the Villa d’Este and the curlew song from Messiaen. Yet these were but passing landmarks in a constantly accelerating explosion of notes.

Mind you, at his finest, nobody is better than Pierre-Laurent Aimard, whether it be Bach or Ligeti. Nobody has such impeccable finger-work, control, transparency, such crystalline articulation in the most quantum-flashed music. Yet when played in one furious opus, the feelings crowded in on one blurring feeling, concluding like supersonic elevator music.

Mr. Aimard’s purpose was not opaque. The four composers of this first half were painting ecstatic colors, their own fierce minds were creating fierce music. And Mr. Aimard obviously believed that we should inhale such fiery genius in a single 40-minute gulp.

The problem was that, while the quartet of composers spoke a similar language, the accents, the meanings the grammar and the sounds were different. So in a sense we were encountering far too many unknown phrases piling onto one another.

It is always wonderful to hear Olivier Messiaen’s augmented bird-sounds, themselves metaphors for more religious feelings. Mr. Aimard lifted us up to the lonely curlew in the remote wetlands, and we were moved. It was equally exciting to hear Scriabin at his late best. Not cryptic, not filled with riddles. Filled with the ecstasy of joy, the jolting changes of rhythms and dynamics. Franz Liszt’s fountains were created for Aimard’s digits, yet for all the spray of notes, he produced color and shadow.

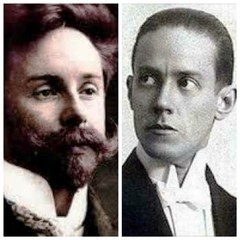

A. Scriabin/N. Obukhov

Finally (or initially), he produced seven short works by Nicolai Obukhov, Russian-born, but an emigrant to Paris after the 1918 revolution. I was totally ignorant of Mr. Obukhov, but his biography was fascinating. When his wife cut his manuscript into pieces he meticulously re-assembled the music–using his own blood to hold the papers together. He invented a 12-tone system of harmony with little knowledge of Schoenberg. And he developed both a new instrument and a new notation using the Sign of the Cross.

Obukhov’s music was mesmerzingly difficult, using the extremes of the keyboard, with sounds like late Scriabin (or the first, Gold Creation with a Messiaen-ic bird call).

Had Mr. Aimard given us Obukhov’s orphic creations, gone offstage for a minute, then continued this way with Liszt, Scriabin and Messiaen, we could have been aural witness to a quartet of varied spiritual productions.

At the end of this first half, though, it was obvious that the audience was applauding Pierre-Laurent Aimard, not the music.

Even after the intermission, so vertiginous were the effects, that the opening Allegro of the “Hammerklavier” seemed to blend in with the first-half works. We had the same drive, the same volatility, the same incendiary plunging ahead.

Obviously it takes a polar difference in mentality between the 18th Century human tornado, and the spiritual storms of composers a century later. And had Mr. Aimard given a first half of, say, Bach and Messiaen and even Chopin, one would have felt the great Beethoven sculpture, even the wicked scherzo, with more singularity.

Finally–finally–with the kernel of the B-flat Major Sonata, the Adagio sostenuto–we had time to catch our breaths. As did Mr. Aimard. He was eloquent, he crafted it well, he didn’t lose a note or a phrase...

Yet not once did I feel that he was reaching under the music, reaching for depths unwritten. I rarely think of other interpretations when listening to a master pianist essay this work. But oh how I longed to hear a scratchy “Hammerklavier” recording by Schnabel or Richter, where a single pause could signify the same spirituality as Messiaen at his finest.

The finale was knotty, complex, more contrapuntal than Bach, more intense than any previous Beethoven. Mr. Aimard gave it propulsion and his miraculous digital clarity, yet it seemed more an intense exercise than the diabolic scheme of Beethoven himself.

Again, the applause was loud in volume yet somehow less than with heartfelt enthusiasm. Mr. Aimard responded with some cryptic notes and silences by György Kurtág.

Not that I have anything against Kurtág, but this was the first pianist I ever heard who felt he needed to give an encore after the “Hammerklavier”. Aimard is a master pianist in every sense of the word, but Beethoven–great Beethoven– should suffice as both “Sanctus” and “Amen”.

Harry Rolnick

|