|

Back

Magicians of the Storm New York

Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium, Metropolitan Museum of Art

03/27/2015 - & March 28, 29, 2015

Gotham Chamber Opera Presents

Henry Purcell: Incidental Music to The Tempest (Attributed)

Kaija Saariaho: The Tempest Songbook (American and World “stage” premieres)

Jennifer Zetlan (soprano), Thomas Richards (Bass-baritone), Dancers from Martha Graham Company: Peiju Chien-Pott, Abdiel Jacobsen, Lloyd Mayor, Xiaochuan Xie

Neal Goren (Conductor)

Luca Veggetti (Director/Choreographer), Clifton Taylor, Luca Veggetti (Scenic Design), Peter Speliopoulos (Costume Design), Clifton Taylor (Lighting Design), Jean-Baptiste Barrière (Video creations)

J. Zetlan (© Richard Termine)

“These our actors,/As I foretold you, were all spirits and /Are melted into air, into thin air”

Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act IV, Scene 1

Shakespeare has his armies of Harold Blooms and Anthony Burgesses, analysts, philosophers, clever semanticians and cunning linguists, actors and directors, psychologists and psychoanalysts, and they are all necessary. Rare, though, are the poets who see Shakespeare as their own, and bring out that ineffable mystery about which only the Bard might have had an inkling.

The Gotham Chamber Opera has made a stab at showing portions of his final play, The Tempest, not as a conundrum of semiotics and clues, but as a magic, about which no solution is desired. This is not the full Tempest, of course, but each element, character, song, movement on the stage adds another cryptic element to the patina of mystery.

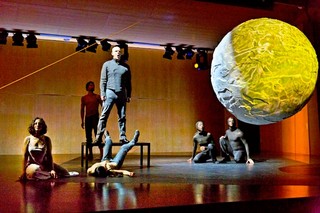

Had they used Henry Purcell’s music alone, it would have simply been a 17th Century masque. Had they only used Kaija Saariaho’s Tempest Songbook, we would have been transported out of Shakespeare into our own century. And while only two singers essay the Purcell/Saariaho music, the stage is always busy (maybe too busy) with dancers, illusions, the ancient orchestra and a large globe which reflects both sounds, faces and signs.

One could compare this to last week’s dramatization of Kurtág’s Kafka-Fragments, where the music (one soprano, one violin) took on different characters with every one of the 40 fragments. Director-Choreographer Luca Veggetti couldn’t have done this here. Kafka was a disconnected fragment. The Tempest needed something approaching the complexity of the original play.

The music, unquestionably the apex of the production is discussed later. The dramatic motions were a paradox. Mr. Veggetti’s stage had six sections from which we could look and feel and hear. Unfortunately, only the most confirmed multitasker could look at it all.

On two sides were screens with the words to the songs (hardly necessary, since both Jennifer Zetlan and Thomas Richards were remarkably clear). Then came the eight-piece Gotham Chamber Opera Orchestra (string quartet, bass, recorder, archlute and harpsichord). In the center, lounging or walking or posing, were the two singers, acting the solo character roles of Ferdinand, Prospero, Caliban, Miranda and Ariel. Behind, around, in front, were four dancers from the Martha Graham Dance Company. On the wall the simulation of an eclipse of the sun, which frequently disappeared.

Whew!

And if that wasn’t enough, the stage was dominated by large hanging globe made of...well, at first it seemed like rough papier-mâché. Before the action, it began to rotate, showing islands, lines which could have come from a moon-map. As the Purcell Chaconne began the evening, those sounds were translated into lights. As the singers sung, the faces were transmogrified vaguely up to the globe, along with the dancers. We saw hands, faces, feet, those geographical lines again...

The globe was hoisted once, descended, then was bounced back and forth for the happy ending (Purcell’s See, See, the Heavens Smile). Mainly it was used for the visual projections of singers and dancers as they strutted and fretted their hour upon the stage.

Now initially, I felt frustrated, not being able to look at everything simultaneously. Did they need all that choreography? Illusions? Eclipses? Perhaps not. Perhaps this was busyness in the extreme. On the other hand, rather than taking everything in, it was possible to get a general picture of the stage, glance up at the globe and listen...just listen.

This was the secret for watching the Gotham Tempest Songbook and of finding a new Shakespeare as well. Neal Goren and the chamber group were suitably authentic (it only took a few seconds from the opening to realize that this was not crisp and bright, but with authentic solemn dark colors). The dancers were certainly athletic. They augmented the stage performance adequately enough, though I confess that their aesthetic gyrations sometimes diverted from the music.

The director/choreographer/co-designer Luca Veggetti might have been happier with a more compact stage, where the movements were more intense, more interrelated, more physically emotional. But for what he had in the gorgeous Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium, he produced never-ending action. (Only one fault: Jennifer Zetlan is an amazing singer, but she is not a Martha Graham dancer, and when one dancer hoisted her up, the difference between their talents was all too blatant.)

Even more staggering were the video effects on the globe by Jean-Baptiste Barrière. From abstractions to visages, silhouettes and orchestral colors, one could easily rename the venue as the Second Globe Theater.

The center was the music. Not only significant, not only totally original, but with the psychological meaning which Shakespeare would thrill to, innately.

First the songs (perhaps by Purcell) and dances (yes, by Purcell). This was typical theater music for a 17th Century Tempest which had probably been Bowdlerized and cut. But the instruments (most of which had been used a century before the original Globe Theater) were not only effective, but in the song, Dry Those Eyes produced with real feeling.

The increasingly estimable Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho understands, more than any living composer, how to create an atmosphere. Sometimes religious or literary, but mainly in terms of dreams. The Tempest Songbook, written a decade ago for singers and a flexible instrumentation, is basically a dream anyhow, no matter how the scholars give it reality.

In this case, Ms. Saariaho had checked her modern instruments at the door, and proceeded with the same beguiling songs–songs which were sometimes quasi-recitatives, sometimes a kind of sprechstimme, often pure melodies–using Mr. Goren’s chamber orchestra. Whatever one might imagine about this strange merger, it worked. Nor, because of the orchestral colors, did one feel any disconnection between the two genres separated by four centuries.

Specifically, Ms. Saariaho had eschewed the scholars who interpret The Tempest as a historicalreality. She sees it as a dream. Neither the words nor the music are kabalistic, but with each emotion–dream, lament, vision, comfort–her music was the background for voices which came out of a wilderness. Hers was neither the literary nor the dramatic Shakespeare, but the notes and images which came from the playwright’s Amadeus-like “taken from God” spirit.

J. Zetlan, T. Richards, Dancers P. Chien-Pott, A. Jacobsen,

L. Mayor, X. Xie (© Richard Termine)

I had never heard Thomas Richards before, but his voice resounded around the stage and the auditorium. Beginning with the hollering Bosun call to the dream of Caliban and the final Purcell-ised duet at the end, his is a voice which is simply commanding.

As for Jennifer Zetlan, I heard her first in Steven Stucky’s opera The Classical Style in a multiplicity of roles, and frankly couldn’t wait to hear her again. While expecting her to essay Ms. Saariaho’s difficult melodies, I hadn’t expect such a purity of voice, of exquisite articulation in the Purcell songs. Her own forward, direct soprano with the dominating voice of Mr. Richards gave life, a sensory feeling to the Gotham’s Tempest.

And as in all the Gotham Chamber Opera works, this could be considered experimental. But that word is more fit for scientists than artists. Shakespeare’s words and structures were also experimental. The substance, though, was always poetry, as was the frequently-achieved goal of this most imaginative production.

Harry Rolnick

|