|

Back

Mr. Adams Creates His Own Scheherazade New York

Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center

03/26/2015 - & March 27, 28, 2015

Anatoly Liadov: The Enchanted Lake, opus 62

Igor Stravinsky: Petrushka (1911, original version)

John Adams: Scheherazade.2 (World Premiere)

Leila Josefowicz (Violin)

New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Alan Gilbert (Music Director/Conductor)

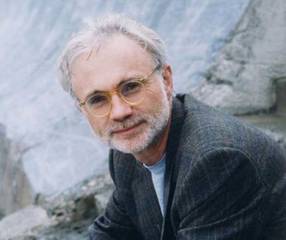

A. Gilbert/L. Josefowicz (© New York Philharmonic)

If Alan Gilbert was looking for an exotic program, he got it last night with the New York Philharmonic. An imaginary “cold evil forest lake”, with “dead nature as fantastical as a fairy tale.” A puppet who comes alive in 1830’s St. Petersburg, insanely jealous. And finally, that most exotic of all characters, Scheherazade. Except in this case, not the original Scheherazade, wondrous as she could be. But composer John Adams’ recreation of the story-teller in a totally new incarnation.

Scheherazade.2 (Dramatic Symphony for Violin and Orchestra), New York Philharmonic Co-Commission, was the cynosure work of the evening, a world premiere 40-minute violin concerto by John Adams, one of the two or three American composers who can be considered avatars of inspiration. True, he does not call it a concerto, but confesses to using the Berlioz term: “A dramatic symphony”. And where a lesser composer would “update” the creature of the Thousand and One Nights, John Adams puts this new Scheherazade into timeless four-movement headings,each with their esoteric meanings.

The titles, like those of Rimsky-Korsakov’s classic, are hints and nuances, not to be taken literally. And in only one of the sections does one feel an anger, a vengeance, an acerbic sense of revenge. We get to that in a moment.

The piece itself was played by another avatar of contemporary music, Leila Josefowicz, who, when asked to describe her in a short talk before the performance, Mr. Adams said “words fail me” about her fearless talent. And yes, this was the way the young Canadian-American virtuoso faced Scheherazade, with passion, melody, dreams when necessary, but always with total commitment to the piece itself.

One didn’t worry about structure for each movement. Since his long-ago days as a “minimalist”, Mr. Adams’ inspiration, his talent for long melodies, and his colorful instrumentation have put him in a different category. Here, the orchestra was a large one, with a cymbalom-player parallel to Ms. Josefowicz in front of Mr. Gilbert.

In a way, although Mr. Adams mentioned only Rimsky and Berlioz in his introduction, the ghost of Richard Strauss’ Heldenleben violin solo was behind each of the movements. One felt this so deeply in the second “A Long Desire (Love Scene)”, where Ms. Josefowicz’ beautiful violin was romantic without being at all schmaltzy. The orchestra started with a kind of “urban” introduction, and the soloist took over from there, with those cantilena drawn-out lines, going up in an arc to a dazzling crescendo.

But the opening “Tale of the Wise Young Woman–Pursuit by the True Believers” had its own atmosphere, starting with an orchestral hubbub, continuing only those lyrical lines, and continuing with the partnership of cimbalom and orchestra.

If one remembers any single movement, it was number three, whose cryptic title might have a more subjective meaning. It deserves its own paragraph:

“Scheherazade and the Men with Beards (doctrinal disputes–they argue among themselves–the judgment–Scheherazade’s appeal–the condemnation.”

J. Adams (© Courtesy of the artist)

Now it would be churlish to imagine that Mr. Adams was depicting the illiterate cabal of rabbis, cheap politicians (actually I don’t have the exact quantity of dollars they take for their votes) and Manhattan tycoons who screamed and whined against his Death of Klinghoffer last year. Perhaps, the “bearded ones” were Sikhs; perhaps the beards were metaphorical.

On the other hand, if Richard Strauss could attack his critics literally by name in Heldenleben, then Mr. Adams had every right in this nasty funny movement (including horns which could have been shofars) to do what he wished.

This began with the chaotic chords of the Beethoven Ninth finale, but then generated a prickly, bristly orchestral pattern against which Ms. Josefowicz added her prickly comments, along with some meditative solos and a few measures at the end without any vibrato at all.

As if she was sick of all their pharisaical casuistry and wanted to get on with the show.

The last movement, “Escape, Flight, Sanctuary”, again brought those lovely passionate lines, this time with the full orchestra changing into an almost reverent, quasi-modal section and ending with the soloist on the highest notes all by herself.

While difficult to describe, this work never once was tedious, never had moments to fill. And just because it \is a complete work, because it never hinted at a “story”, the piece had an epic quality about it. One might not have remembered many individual moments (except in the picturesque third movement), but one never felt that this was anything less than music which had behind it a grand and glorious vision.

Mr. Adams’ original conception was not to produce a picture of the emancipated woman, updated from the Arab-Persian classic books. As in his operas, his beliefs are secondary to his poetry, his dramatic situations and their development. This is what he did with Sheherazade.2. His inspiration never seems to flag, and the result was a gorgeous picture which–while never superseding–is a genuine sequel to the Russian original of 137 years ago.

Actually, the program did begin with a kind of Rimsky-Korsakov piece by that lackadaisical procrastinating miniature colorist, Anatoly Liadov, who could be considered the poor man’s Rimsky. The Enchanted Lake is hypnotic, and so solitary that any hint of an audience subtracts from its effects. I am not averse to concert halls, but not even Alan Gilbert can take this Liadov out of the shadows.

On the opposite side of Liadov is Rinsky’s student Igor Stravinsky with the original version of Petrushka. Thanks to Soviet copyright laws, Stravinsky had to revise the 1911 Petrushka. The result was hardly a chamber work, but it never had the oomph, the grand and glorious and huge orchestral resources of the original.

Mr. Gilbert let his orchestra come... well, not loose. But with discipline, with fabulous piano solos by Eric Huebner, some terrifyingly good snare-drum riffs and all the players geared to the nth degree, this was a grandiose Petrushka. That nasty little eponymous puppet would have been proud.

Harry Rolnick

|