|

Back

New York

Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center

02/03/2015 -

Nebojsa Jovan Zivkovic: Meccanico from Trio per uno for Percussion Trio

Conlon Nancarrow: Piece for Tape arranged for Percussion(arranged by Dominic Murcott)

Thierry De Mey: Musique de tables for Percussion Trio

John Cage: In a Landscape for Marimba (trans. Ian David Rosenbaum)

Tôru Takemitsu: Rain Tree for Percussion Trio

Steve Reich: Drumming: Part 1 for Percussion Quartet

Béla Bartók: Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, sz. 110

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center: Victor Caccese, Christopher Froh, Auyano Kataoka, Ian David Rosenbaum (Percussion), Gilbert Kalish (Piano), Wu Han (Piano)

C. Froh, A. Kataoka, I. D. Rosenbaum in Meccanico (© Hiroyuki Ito)

Two evenings of alleged “chamber music” broke the rules this week. Monday, a pair of violinists and one violist played the most tuneful Central European compositions in the highest treble. Last night, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center again broke the mold by going to rock bottom–percussion! No, it wasn’t all bass drum, and the instruments did include a highfalutin’ piece o’ percussion called, I believe, the “fortepiano”. Yet from the beginning, one had the feeling–a misplaced feeling–that this would be an evening of pounding, beating and hammering.

In fact, the first work did have the three amazing percussionists, Christopher Froh, Auyano Kataoka, and Ian David Rosenbaum pounding and beating out non-stop ritual ersatz African drumming in the appropriately named Meccanico by the Serbian-born Nebojsa Jovan Zivkovic. Mr. Zivkovic is himself an accomplished percussionist/marimbist, but this was–with the exception of a china-gong–pure drumming.

Within six harsh minutes, these three virtuosi worked on bongos and a bass drum, in tandem, apart from each other, but always with the virtually oppressive rhythms that I thought would continue through the entire concert.

That was obviously wrong, since the following solo three-minute work was by marimba soloist Froh, and was kind of a trick. Conlon Nancarrow had written only a single work for tape recorder in the antediluvian 1950’s Known for its superhuman speed, it was shelved away but recently discovered, and “humanized” for several percussion instruments. For its third incarnation, a single marimba was the instrument, and, yes, played with superhuman speed by Mr. Froh. But one would expect little else from one of these players.

By far, the most sheerly outré–oh, hell, the kinkiest work was Thierry De Mey’s Musique de Tables. The title itself should called for an introductory anthem of Chuck Berry’s Roll Over, Teleman. For Georg Philip was the inventor Tafelmusik, and no doubt he would have been fascinated to see the sixty dancers–all the fingers from three drummers–tripping the light fantastic on a single table.

The Belgian composer’s music was first of all an audio lollipop for players and audience. The players were told to use their hands to make their table sound like “castanets”, “a stone”, “windshield wipers”, “a fan”. All of this was signified in their scores, for which they dutifully turned over their pages to the joy of the full house.

But with these sounds–sometimes simultaneous, sometimes contrapuntal, sometimes conversational like an Elliott Carter quartet–their hands danced together on that table. Sweeping across the table, snapping down, and sometimes (shhh) cheating by clapping!

The program notes describe this as a Baroque suite, with rondo, fugato etc. but so entranced was I with the six hands of Messrs Froh, Kataoka and Rosenbaum, that I forgot to check the structure. Next time for certain.

Two works were less gleeful, and more transporting. John Cage’s original dance In a Landscape was transcribed for marimba by its player, Ian David Rosenbaum, and sounded far more like Ravel than Cage. Which was fine for this listener. Always soft, lulling, with one phrase repeated over and under and in between and equally lulling theme, this was by far a more mystic Cage than his usual algebraic profundities.

The other absolutely entrancing work was Tôru Takemitsu’s Rain Tree. Cage’s work depended upon a calming melody, a linear direction for the mind. Takemitsu worked with sound alone. First the sounds of tiny antique cymbals, played with silken delicacy. Added to that the bell-like vibraphone, then the woody sounds of the marimba. Takemitsu said it (and those three produced it) better than I ever could: “Listening to my music can be compared to walking through a garden and experiencing the changes in light, pattern and texture.”

The compass of the concert led from unknown composers to more familiar names, and Steve Reich is familiar not only as a composer but originally a drummer as well. Not satisfied with his education in America, he traveled to Africa to study his art, returning with several highly interesting works.

I had heard his early Study for Pieces of Wood which had only sticks, beating out tattoos on different fabrics and textures. If the sounds were more gamelan than African, that hardly subtracted from its effect.

Last night, part of his Drumming had tones–or what I thought–were tones, coming from four pair of tuned bongos, played by that magnificent trio plus Victor Caccese. What Mr. Reich produced was both differences in depth (as one to four players worked the bongos) and in those tones. But this was not melody. Somehow, the different notes were shown through the instruments. The 15 minutes of drumming–by far the longest work in the first half–was never too long. The tapestry of beatings was unremitting, but, in painting terms, we experienced textures which seemed the same, were altered almost invisibly (helped by actually watching the players taking their turns) and whose hues/notes were seen and heard far underneath the dominating sounds themselves.

Personally, it was sad seeing these percussion soloists leave their standout posts, but the second half, devoted to Bartók’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion put them into a supplementary position.

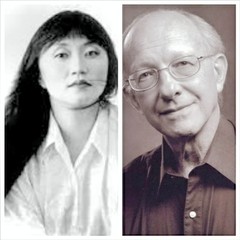

W. Han, G. Kalish (© Courtesy of the Artist/Christian Steiner)

The pair of pianists included the co-director of the Chamber Music series, Wu Han, and one of the giants of the New York piano scene, Gilbert Kalish. Ms. Han played her music from a computer-tablet on the piano stand, while Mr. Kalish worked the old-fashioned way with a score and a page-turner. Otherwise, they played in tandem, and their own experience made the work pretty vibrant.

That, though, was due to our percussionists, standing behind the pianists, with a whole battery of their instruments in tow. I counted three timpani, a few snare drums, a cymbal or two and some tam-tams, all handled with conservative good taste.

This might not have been enough, though. Bartók needed a so-strong rhythmic impetus underneath the dizzying playing, the clusters of notes, the sounds. Messrs Kalish and Han were fine in their performances, generous in their massive sounds, but for some reason–perhaps the too equitable audio in Alice Tully Hall–the exhilarating excesses were relegated to the point of superb playing and good taste.

Nobody could deny this was a fine finale to this extraordinary evening, yet one wished it was less chamber enchantment and more organic exuberance.

Harry Rolnick

|