|

Back

Bringing Melody from Madness New York

Isaac Stern Auditorium, Carnegie Hall

11/19/2014 - & October 29, 30, November 1 (San Francisco), 13 (Ann Arbor), 18 (Princeton), 2014

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 7 in E Minor

San Francisco Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas (Musical Director/Conductor)

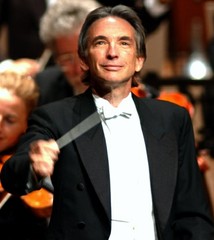

M. Tilson Thomas (© michaeltilsonthomas.com)

“It’s a mad, mad, mad, mad symphony”, wrote that great Mahler-ologist Deryck Cooke about the Seventh. And accepting that premise, the corollary should be that one succeeds by conducting it as a piece of inspired insanity.

That’s obviously wrong. This isn’t madness Van Gogh or Schumann style. Gustav Mahler knew what he was doing, even if an older generation of conductors were proud to be confused. But the always youthful Michael Tilson Thomas perceived the Seventh as neither skewed or as insane, but more like an El Greco painting. The distortions of the musical world made that world even more interesting. And if one chose not to “understand”, but to experience, then one could experience Mahler at his most radiant.

This, the first of two San Francisco Orchestra concerts, showed an orchestra which was never daunted by the work. A few fluffs on the horns were inevitable, and were quickly forgotten next to the effulgent brasses in the finale, the solo strings in the mysterious fourth movement, the pinpoint counterpoint of harp and timpani in the third movement–and the extreme bitonality of the opening movement.

That, in fact, is the only movement that can be called “mad”, as it lurches from one mood to another, and it takes a man (and an orchestra) to follow through the troughs and waves, the halcyons and the anarchic harmonies to come to a conclusion. But the sure-footed tenor horn which started the symphony gave the signal, and Mr. Tilson Thomas, without a stop, plowed through the score. No wondering, no attempts at making sense of the movement, but, like that physics axiom, giving the push, allowing the momentum to take its own course.

This has always been the most enigmatic section, and one realized under Mr. Tilson Thomas’s baton, that the harmonies were more than eccentric, they were truly a harbinger of the Schoenbergian future. Done without rules or regulations, but erupting deep from Mahler’s mind.

Next to this, the second and fourth sections–the night and the walk–were given a more gentle treatment by the conductor. Yes, the Allegro moderato was a march, but more a children’s march, marching in the shadows but lacking the mystery of the shadows. To Mr. Tilson Thomas, the darkness was simply a painting of eerie things, they were never meant to scare.

And the pinpoint harp/drum motives from the gorgeous fourth movement were equally…well, not exactly lulling, but giving a sense that even nightmares are things from which we waken.

The scherzo was no joke either. But Mr. Tilson Thomas gave it an almost aristocratic confidence, the instruments passing their notes from one to another (a harbinger of Webern?), with the San Francisco Orchestra again painting its colors.

As for that finale, one imagines that any conductor who can get through the first four sections sees this as light at the end of the flower-filled tunnel. Mr. Tilson Thomas didn’t worry about those Wagnerian allusions. As in the opening, the brass, the popular songs, the easy tonic-dominant melodies their nudge and let the orchestra do the rest.

At the end, I realized that the Seventh’s so-called madness is that one cannot classify the symphony. It isn’t about death or resurrection of nature or poetry or heavenly perceptions. The Seventh Symphony is about itself. And those extra-musical allusions are the stuff of musicologists and critics, not composer or conductor.

This was the way Mr. Tilson Thomas saw it. He made no effort to tie things together last night. The music, not descriptive in verbal terms, was its own reward, and the conductor was obviously pleased to wrap this gift with well-deserved glory.

Harry Rolnick

|